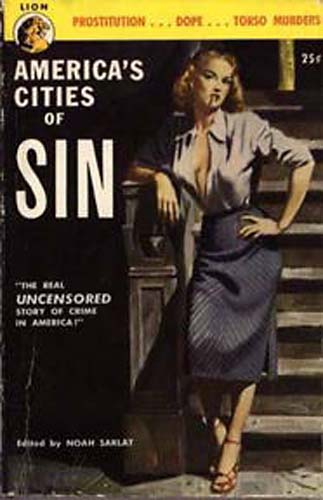

America’s Cities of Sin

Chapter 3: “Baltimore’s Bawdy Block”

by Stephen Hull (Copyright Stag (1952))

THE OLDEST, lushest, bawdiest tenderloin in the United States today is that back-of-the-waterfront area of Baltimore, Maryland, known as “The Block.” Actually the district covers about three blocks along East Baltimore Street, one block down from the great Patapsco River docks that have made the Maryland metropolis America’s second port in tonnage. From Holliday Street on the west to the Fallsway on the east, East Baltimore Street is a garish, neon-lit artery dotted with burlesque shows, penny arcades, tattoo parlors, saloons, cheap hotels fifth-rate movies, night clubs and shooting galleries. This low-down amusement sector roars full blast from mid afternoon to 2 A.M. At that time the legal closing hour for the sale of liquor jet-propels the customers from the strip-tease joints out on to the street to pick up girIs and taxi off to the broad minded hotels in the neighborhood, or to the dives around lower Broadway where after-hours hootch is available in teacups.

This Baltimore Barbary Coast has the longest, continuous history of any honky-tonk area in the country. Chicago’s North Clark Street Rialto dates back only to the latter years of the last century; and New Orleans’ Bourbon Street was a respectable Vieux Carre thoroughfare 100 years ago. But marines, fresh from the shores of Tripoli, and the jolly jack-tars of Admiral John Paul Jones’ navy roistered through the grog shops and dance halls of ‘The Block,” with soft-spoken, hard-drinking floozies from Fells Point on their arms, 75 years before the California goldrush and 35 years before Chicago had a single inhabitant.

Fells Point, named after an 18th century merchant and shipbuilder, was the old name of the waterfront tender-loin. The first market area in town was there, where lower Broadway met the Thames Street docks, and to the rest of the community, The Point was known as “Sailortown.” Even then it had a steamy reputation; its dancehalls, sailors’ boarding houses, taverns and inns providing a favorite slumming place for Baltimore’s upper crust, who came down to “Sailortown” to gape at the bearded sea-men and their trollops as they sang, danced, gambled, and made love in full public view.

As time went on, the center of the tenderloin shifted slightly westward along Baltimore Street, never getting more than a block from the docks until, by the late 19th century, it was occupying its present location between Holliday Street and the Fallsway (old Fells Point). From earliest days it was absolutely uninhibited and, to date, Baltimore remains just about the only large city in the country which has never experienced at least one major reform era. “The heat” which has periodically closed down the tenderloins of Chicago, San Francisco and New Orleans has never amounted to more than a balmy breeze in Baltimore, a town which is extremely partial to good beer and fast horses.

Baltimore’s great fire of 1904 wiped out most of the tenderloin along East Baltimore Street; such old landmarks as Pearce and Scheck’s Nickelodeon Theatre, Arthur Humbert’s Penny Arcade, Filling’s Basement Wine Room (champagne 10 cents a glass) and Jake Goldberg’s Dancing School going up in flames. Phoenix-like, from the sinful old ashes arose “The Block”. Back too, came the wine rooms, the penny arcades and the nickel-odeons. Competition between the latter grew so keen that the houses presented animal shows in the lobby and gave away pianos. The new tenderloin even took on some opposition territory; the Church of the Messiah, on Baltimore Street, being converted into a theatre for Presenting the “new” craze — motion pictures. Today, as the Rivoli Theatre, the old church reverberates to the soundtrack hoof-beats of a dozen different horse-operas per week.

“The Block’s” central structure today, is the Gayety Burlesque Theatre. For more than 40 years, Baltimore men have stagged it to the Gayety on Friday and Saturday nights while their wives played bridge, knitted and gossiped. The Gayety itself is not just another burlesque show. It is also a saloon, pool hall and night club. The pool hall is upstairs, over the theatre; the saloon and night club are in the basement It is about the only burlesque house in the country where alcoholic beverages are for sale on the premises. Until about six months ago, the house was a part of the Eastern Mutual Burlesque Wheel; then it was sold to the same outfit that runs the Casino Theatre in Boston.

The Gayety Night Club, in the basement, is a strip-tease joint with a tiny stage at one end of the bar. The club starts up when the last show is out upstairs and goes on until the 2 A.M. curfew on liquor sales. Thus, it is possible for a customer to start in at the Gayety at noon, ogle peelers all afternoon, have a couple of drinks and a sandwich, shoot some pool and do more drinking and ogling in the night club until 2 A.M. In fact, it has been alleged that a pair of sailors once lived in the Gayety for four days while a Shore Patrol was looking for them.

The Gayety Night Club is still run by John (Hon) Nickel, although he sold the burlesque end to the Boston outfit. He is an old hotel man who found himself in the theatrical business, back in 1921, when a burlesque troupe went broke while staying at his hotel. Hon took over the troupe, leased the Gayety, ran it successfully for almost 80 years.

The show at the Gayety can get pretty rough after the cast and audience have shared fellowship at the bar a few times. But it is mild compared to the goings-on in the two tiny burlesque houses across the street — the Clover and the Globe. These joints, popularly known as “scratch houses,” feature two ancient movies and five or six semi amateur strippers. The band at both scratch-houses consists of a piano player and drummer. One of the features of the show is a long intermission pitch for filthy books, pictures and “novelties.” Sailors, seamen, dockers, industrial workers and teen-age kids seem to make up most of the audience at these emporiums of joy. They think nothing of shouting at the performers who frequently reply in kind. On stage, the girls quickly take off everything. The Globe advertises its show as “the meanest, most low down burlesque in the world.” Check.

The same outfit seems to own both of these joints, and the casts appear to be interchangeable. Outside of the girls, working the scratch houses looks like a lifetime job; two comics named Miles (Cohen) Murphy and Billy (Dutch) Schultz have worked steadily for close to 20 years. When they are not on stage they double as barkers in front of the theatres. A whole generation of Baltimore men has grown to maturity without ever having seen any other comedians at the Clover or Globe than Miles and Dutch; they, like Hon Nickels, are town characters.

In addition to the Gayety Night Club, there are 13 other cabarets in “The Block” dispensing entertainment, most of it strip-tease. Some of the more popular are Kay’s, the Miami, the Two O’Clock Club, and the Oasis. Kay’s and the Miami are low joints with the peelers operating practically in the laps of the customers; the former is currently featuring Puerto Rican gals who have calypso and the rhumba for bumps and grinds. “Moana” is the feature of Kay’s show with a dance in which one-half of her, dressed like a man, seduces the other half, not dressed at all, to speak of, but obviously female. At the Miami, the m.c. is a very feminine gent whose specialty is jokes about perversion. Hostesses, performers and B-girls solicit the customers for drinks or anything else that may occur to them. In one club the writer saw the bar tender serve ginger ale to two B-girls who called for “gin.” The sucker with them paid for gin, of course.

The Two O’Clock Club, sandwiched in between the Globe and the Clover, is the most respectable cabaret in “The Block.” It has a Chicago type “burlesque bar” and high-hats the local talent featured elsewhere in the Tenderloin by importing “name” strippers from New York like “Zorita,” “Syra” (“Most Beautiful Girl in the World”), and “The Wow Girl,” Jessica Rogers.

One of “The Block” spots has a national reputation. This is the Oasis, the only night-club in America solvent enough to be listed in Dun and Bradstreet. From 1927 to 1945 the Oasis was operated by a jovial character named Max Cohen, and was so successful that Max has been able to buy the entire block in which the cabaret is located. The place has a staff of more than 100 and, next to the Gayety Theatre, is Baltimore’s most popular stag hang-out. It caters to an uptown crowd and frowns on the waterfront riff-raff that patronize the Miami and Kay’s, although the floor show is the same lowdown rump-shake that is featured in the other two dives. But just so as not to offend anybody, Max opened up a joint upstairs in the Oasis which he called Harry’s Bar and welcomed the unshirted who were persona non grata in the down-stairs room. Harry’s has a floor show in keeping with its cheaper clientele.

When Max took over the Oasis in 1927, he had the entire room redecorated by a couple of local artists who were on their uppers. The boys turned it into a sultan’s paradise with sultry-eyed, bare-bosomed houris smiling down from a background of camels, tents and sand. Max had no dressing rooms for his performers at that time, so he let them change clothes off in one corner of the club, in full view of the customers. This novel arrangement was an instantaneous hit. He also capitalized on the lack of talent in the revue by advertising it far and wide as “the worst show and the best time in the world.” This cagey promotion, plus the anything-goes atmosphere of the place, soon ganed it a national reputation and theatrical stars took to dropping down to the Oasis when they were passing through. John Barrymore once recited Hamlet’s soliloquy there, and a national news magazine dignified the club with a write-up. Senators, Congressmen and assorted embassy staffs, fleeing dull Washington week ends, took to making the Oasis their Friday to Monday headquarters. Max was always good to his help, paying them a base salary of $35 per week plus commission on drinks and whatever “tips” they could wheedle out of the customers. Willie Gray, the m.c. who opened the Oasis in 1927, has been there ever since — a 24-year run. Some of the girls have been there almost as long, being taken on as waitresses when through as strippers.

Max is full of cute angles. In 1937 he hired a lady bouncer by the name of Mickey Steele, a six-foot acrobat from the Pennsylvania coal fields. Mickey was always considerate of the people she bounced; first asking them where they lived and then throwing them in that general direction. She was succeeded by a character known as “Machine-Gun Butch,” the current incumbent.

The Oasis has been the scene of some memorable brawls. On the writer’s last visit, a liquor glass, hurled by an irate female guest at Willie Gray, the m.c., grazed his (the writer’s) scalp before thudding into the bosom of a vocalist known as Battleship Maggie, who was standing beside Willie. Maggie, whose chief forte is singing an obscene ballad called “Hot Nuts,” didn’t seem to mind. When a disturbance seems imminent at the Oasis, “Kid Shoofly” takes over. The Kid comes out of a bottle behind the bar and his real name is Michael Finn. He generally quiets things down. If he doesn’t, Machine-Gun Butch comes in. Butch plays pretty rough. Neither Kid Shoofly nor Butch had much to do during Max’s regime, for Max was a fast talker and generally got people to see things his way. On one occasion, he forestalled a hold-up of the club by persuading the heisters that the hold-up concession was held by the house.

Max has always had a finger in politics in Baltimore, and in 1937 he was appointed a Justice of the Peace by Governor Harry Nice. From then on he was known as “the Judge” by “The Block.” But the honor was short-lived as someone got to the governor with the suggestion that Max wasn’t quite the type, and the latter rescinded the appointment.

In 1945, however, Max got a little ahead of himself. He sold the Oasis to one Sam Levin and agreed to get out of the entertainment business. No sooner had Sam taken over than Max bought the Miami and began applying the Oasis formula to that club.

Not the least of ‘The Block’s” attractions are the many pin-ball arcades and tattoo parlors. Most of the former feature contraceptives, Polish sausage, orangeade and dirty pictures. The largest of the tattoo emporiums was established by a Baltimore Street character named Frenchy De Saule, who shared with Hon Nickels and Max Cohen the distinction of being a “Block” personality, known all over town. Frenchy had at one time been a pupil of the world’s foremost tattoo artist, Robert Sommers, and Sommers had paid Frenchy the compliment of executing his masterpiece, “Day of Judgment” on Frenchy’s back. Frenchy’s own masterpiece was the entire British fleet tattooed on a British sailor.

“The Block” is today what it has always been — a hang-out for the town’s politicians and gamblers. The mayor’s office overlooks the area, and the Miami Cabaret is located right next door to the police station. Most of the politicians and gamblers eat at Horn and Horn’s restaurant in “The Block,” while ward heelers, bookies, numbers runners, and lesser lights dine at Bickford’s cafeteria, also known as “No.10 Downing St.”

Old Baltimoreans are likely to be sentimental about “The Block,” the town has a congenital dislike for reformers and prudery. But the plain truth is that “The Block” is about as vicious and lawless an area as it is possible to find in this country. Narcotics are openly sold there, indecent entertainment is the rule rather than the exception, prostitutes solicit without hindrance in the bars and night clubs, and no real attempt is made to keep teen-agers out of burlesque.

Baltimore, of course, has laws and ordinances on the books which empower the authorities to keep “The Block” well under control. But the town is also one of those unfortunate cities which, like Chicago and Galveston, is pretty well entwined in the toils of the nation-wide crime syndicate known as the Mafia (the old Unione Siciliano of the Capone days). Indeed, a recent book states categorically that Baltimore is the best (or worst) example of Mafia control in the country. This means that the city runs wide open.

Baltimoreans like to bet the horses and, therefore, tend to take a dim view of all attempts at clean-up.

So, ‘The Block” goes on today pretty much as it has for the past 175 years; a place where up-town Baltimore can come to be shocked or titillated; where sailors and their gals, reinforced these days by crowds of industrial workers from the town’s new aircraft and shipbuilding works, can disport themselves without fear of interference. But the profit from all this not-so-merry hell today goes into the pockets of a country wide crime syndicate which, as the Kefauver Committee discovered, has its brains in New York, its muscles in Chicago and its greedy fingers in every sub-rosa business in the United States.

Baltimore changes, but “The Block,” like sin itself, goes on forever.

Special thanks to Dr. Chris Grau for archiving and transcribing this chapter on Baltimore history.

I have that book!

Pingback: Jail break…1949 style… | North Carolina Room -- Forsyth County Public Library

Really awesome one.

Grew up in highlandtown…played trumpet and played on the block as a youngster and learned some things…happy times gayety globe, Harrys etc. Ma uncle joe was the mounted policeman on the block..great training ground..as was all balmer at that time.

Pingback: Baltimore, June 18, 2016 | Sagittarius Dolly

My Grandmother owned Kay’s Cabaret! She was Kay. The family didn’t let me know until I was driving age, and she sold the place. I wish I could have seen and experienced it (I guess!). She was an amazing woman and a wonderful Grandmother.

My Grandmother worked at The Oasis in the late 1930s to late 1950s.