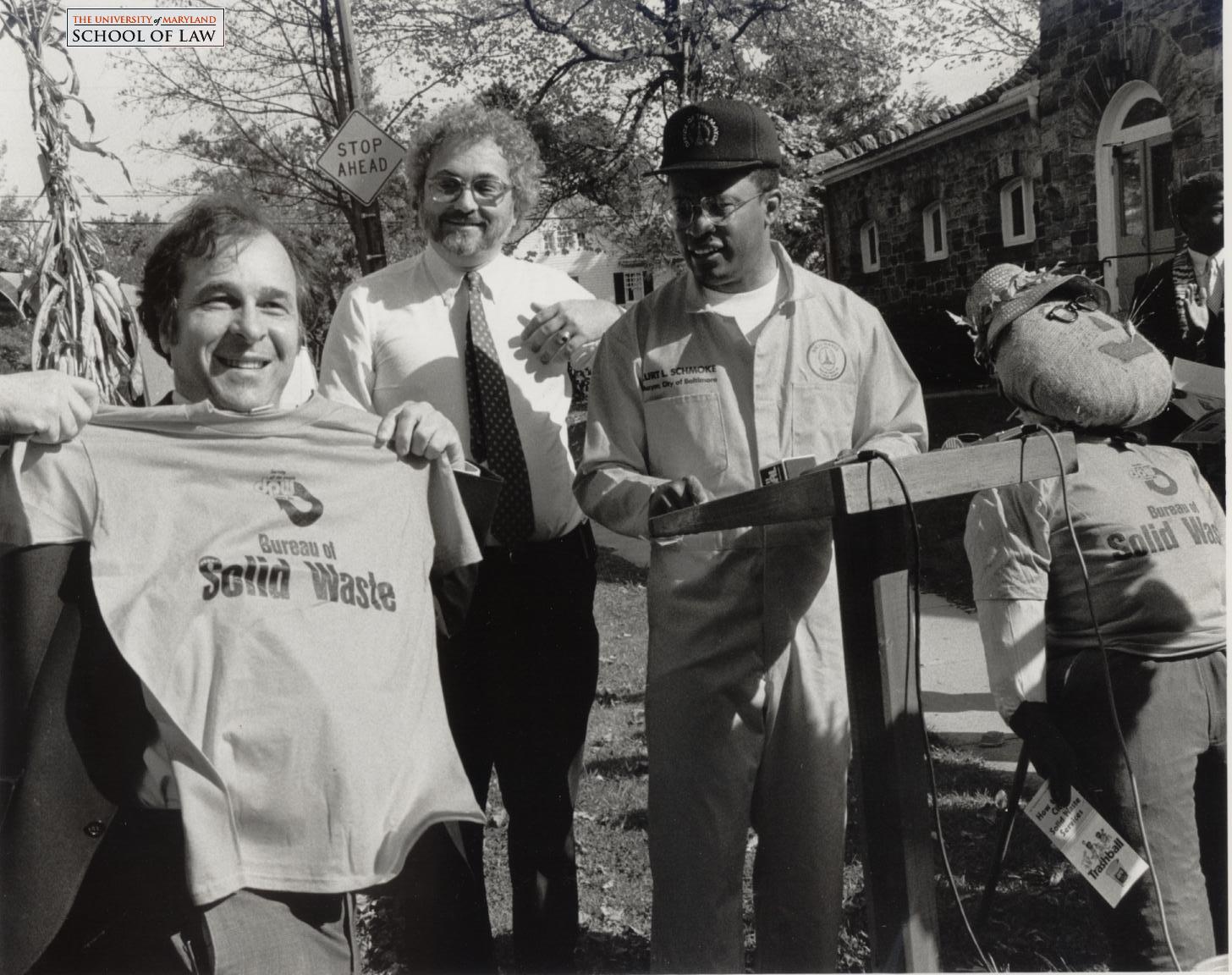

You can’t ignore the fact that Baltimore is a filthy city, ridden with chicken bones, plastic bags, soda bottles and food wrappers. Don’t you think it’s time to bring back “Trashball” — one of the most ingenious “stop littering” ad campaigns ever devised? Teach a kid that throwing away trash is the right thing to do, that’s it’s cool, that it’s fun, that it’s a “sport” — make it a teachable habit that a kid will carry on into adulthood. And teach the adults too! Hire a rap star to update the “Trashball” theme, have Ray Lewis and other Ravens tackle the litterbugs and put trash in its place. It can be done!

You can’t ignore the fact that Baltimore is a filthy city, ridden with chicken bones, plastic bags, soda bottles and food wrappers. Don’t you think it’s time to bring back “Trashball” — one of the most ingenious “stop littering” ad campaigns ever devised? Teach a kid that throwing away trash is the right thing to do, that’s it’s cool, that it’s fun, that it’s a “sport” — make it a teachable habit that a kid will carry on into adulthood. And teach the adults too! Hire a rap star to update the “Trashball” theme, have Ray Lewis and other Ravens tackle the litterbugs and put trash in its place. It can be done!

George Blalog, unidentified individual and, Mayor Kurt L. Schmoke at promotional event for “Trashball,” 1987. Photo by Larry Gibson, DigitalCommons@UM Law.

William Donald Schaefer: A Political Biography

By C. Fraser Smith

He needed comforting around the clock—and got it often from strong, imaginative, and loyal followers even when he abused them. The business management guru Tom Peters, a big Schaefer fan, observed that Baltimore‘s leader had an ability to infuse others with his own passion. People began to see him as a human counterforce against welfare dependency, dysfunctional families, poorly performing schools, and even the American Dream, the magnet pull of single family detached houses in the suburbs. Embry and others thought Schaefer didn`t understand any particular program. They also began to see that it didn’t matter. He was the program, the common element in everything that happened.

He wanted a continual campaign against litter, and, hokey as it seemed sometimes, he pursued cleanliness the way he pursued his other enemies. He raved about how kids in particular seemed to have no idea that they created trash.

“Figure this out,” he said to Bailey Fine one day at a cabinet meeting. She imagined some sort of broad-scale communication would be needed to hammer home the antitrash message. She went to friends at the Ad Council, an organization of local advertising companies. Someone suggested she try VanSant Dugdale, one of the city’s largest ad firms. Dan Loden, a young account executive, was assigned to the project. Together, they concluded that they could transmute refuse into basketballs bouncing loose through the streets of Baltimore, bounding over marble steps like multicolored tumbleweeds to be scooped up and swished into trashcans remade with mesh sides to resemble basketball nets. lf detritus could be dunked, hooked, and shot into these receptacles, it would never become litter. They would call their game Trashball.

Around this somewhat airy and fanciful concept, they commissioned an antitrash ditty and went to New York to have it recorded. A film was made to give the whole thing maximum exposure. Local sports figures were enlisted to be the stars. A collegian named Marvin Webster of Baltimore`s Morgan State Bears basketball team agreed to participate—a very useful thing, because Webster‘s shot-blocking ability had given him the perfect nickname: the Eraser. In this situation, Marvin “The Eraser” Webster would be swatting away trash. The Orioles pitched in too: Al Bumbry, the fleet outfielder; Earl Weaver, the fiery manager; and Jim Palmer; the cerebral pitcher, were among them. They did the Trashball thing in person all over the city from the Inner Harbor to Bolton Hill. They talked earnestly about an element of blight everyone could control. Kids should play this game because The Eraser, Al, Earl, and Jim wanted them to. At some of these events, the dunking, hooking, and shooting went on as the Morgan State Band played in the background.

excerpt from Maryland Public Television’s “Citizen Schaefer”

Schaefer loved it. He went to New York City to see the movie and, when he got back to Baltimore, arranged to have a load of trash dumped at City Hall Plaza so he and other city officials could hone their Trashball skills. He posed beneath the Shot Tower with a huge push broom. Similar events, often starring the ballplayers, were done in neighborhoods throughout the city. The Trashball movie was shown in local theaters. It worked, Fine thought later, because even when people air-mailed their Twinkie wrappers onto the sidewalk, they saw that Schaefer and his crew were working overtime, pumping out ideas, risking their dignity—challenging Baltimoreans to do the right thing. Habits would not change overnight, but the effort had to be made. A willing suspension of disbelief was necessary to pull this off, and people were increasingly happy to oblige.

Fine‘s only regret was buying into an idea that limited the impact of her campaign: Why not charge other cities for what Baltimore was doing, someone said? But, of course, other cities were as strapped for cash as Baltimore was, and few takers appeared. Had the idea been available for the asking, Trashball would have drawn more attention to Schaefer`s city. Nevertheless Fine’s idea became the standard by which other ideas were judged, motivating the City Hall team to think deeply—too deeply, some thought—about other ways to gain the boss`s Favor.

Related Links

Pingback: Dr. Stacy Spaulding Towson University | Mayor Annoyed by Richard Ben Cramer