Graham Chambers System band - Ray Quigley (Rhythm Guitar), Ron Murphy (Lead vocals), Marty Mettee (lead guitar/vocals), Bob Holland (keyboards, John St. Jean (bass), Paul Treffinger (drums)

By Eirik Tecumseh Blom, photos by C. B. Nieberding (Baltimore Magazine, 9/1967)

Eirik Tecumseh Blom —there’s American Indian blood in those veins, along with the Scandinavian — describes himself as “barely a post-teenager.” At 20, he has been a cook, the manager of a hamburger stand, to a house painter, a carver of Polynesian gods; his only previously published work was an article about high school dropouts, from a dropout’s point of view, (he was one), in an educational magazine. This fall, he will attend Catonsville Community College.

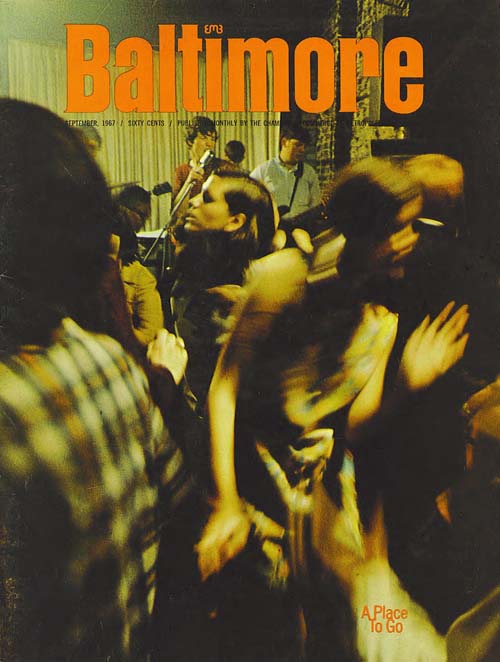

The Bluesette, both incomprehensible and off limits to adults, is so popular with teenagers that hundreds are turned away. Which points up the dilemma: the kids say that there's nothing to do, no place to go, in Baltimore.

Five years ago the big sound in teenage music was The Twist, as made famous by Chubby Checker, and its original temple, the place to go, was the Peppermint Lounge in New York. Like all teenage fads, The Twist faded away, and with it went the Peppermint Lounge. But it was the forerunner of the modern discotheque, a craze that is just now reaching its peak. (The addenda to Webster’s New Third International describes a discotheque as a small, intimate place where people in informal dress dance to records; today the term is very broadly used, and can mean just about any public establishment with music for dancing.)

Over the past two years half a dozen teenage discotheques have opened in the downtown Baltimore area. Only one, the Bluesette, remains. It has survived where others with more money, better advertising and superior locations have failed. Why? What is the secret that only the Bluesette (at 2439 North. Charles Street) seems to possess?

The magic ingredient seems to be the owner, Arthur Peyton. He is 31, but he seems to have avoided what the New York Times calls “the generation gap” — the inability of anyone over 30 to talk to anyone under 30. He is the embodiment of the youth movement, and all that it involves, freak outs, be-ins, happenings. He has not lost contact and, consequently, youth accepts him. “The kids know I’m not just out to make a quick buck,” he says. “I want to’ give them something for their money.”

The fact that he has succeeded in giving them what they want would seem to be a dubious achievement to most adults. Even to those who have been to a discotheque a visit to the Bluesette is an experience, and to those who aren’t in tune with youth and its music, it is probably Everyman’s definition of Hell. Except for a few multicolored, muted Japanese lanterns, there is no lighting. The room is almost pitch dark. There are weird eyes and super-unrealistic paintings staring down from the walls at odd angles. Filled to capacity the place holds 110, but it would comfortably seat only 25. (Nothing alcoholic is served, or permitted: the bar serves only Coca Cola. No adults are allowed in the place as customers, but Peyton invites apprehensive parents who telephone occasionally to come in and have a look, and he suggests to hardcore skeptics that they call the Northern District police stations and check him out.

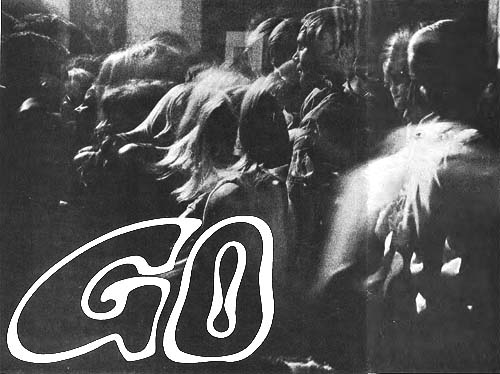

The band is of the new sound, the California beat, and the musicians, all young; play songs made famous by such renowned groups as the Jefferson Airplane, the Mothers of Invention, the Kitchen Cinq, the Seeds, Oedipus and the Mothers, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, the Insex, the Peanut Butter Conspiracy. The musicians dress as outlandishly as any Haight Ashbury hippie, and with the assistance of amplifiers that have been turned up to the threshold of pain invade the being from every direction. Once, at the Bluesette, the sound actually broke a thick mirror.

Peyton calls it “total environment.” He is not exaggerating. After ten minutes all your senses, with the possible exception of that of existence, are dead. The noise is so loud that you can no longer hear. There is only the feeling of it. You are jostled, shoved, and bumped so often that you become numb. Your eyes have just about become accustomed to the dark when they turn off the lanterns and turn on the strobe light, a device that flashes a naked 150-watt bulb on and off four times a second.

You are alternately assaulted by searing flashes of light and plunged into blinding darkness while you at-tempt to dance on a floor 15 feet long and six feet wide. With 80 or 100 other people.

Yet to the kids in Baltimore, this is the place to go. The only place. They go in such numbers that Peyton turns away 300 a weekend.

Downtown is the in-word with Baltimore’s kids today. Downtown is what is happening. Yet downtown has nothing to offer them. Peyton says: “The biggest complaint I get from the kids today is that there is no place to go. Nothing to do.” He is speaking about the kind of kids who are his customers, kids from the best, most stable sections of Baltimore. These are not the mad mods, the hippies in the Haight Ashbury sense, the addicts, the Hell’s Angels. They are the kid next door, whoever he or she might be.

Peyton makes a valid point. Baltimore has no Sunset Strip like Los Angeles. Most people argue that this is good. That places such as the strip have reputations for dope, drinking, free love. That nothing good comes out of a place where the kids run wild. A valid point, too. But the solution that Baltimore youth has found could hardly be called better.

Kids have to have a place to go. On dates it’s easy. Movies. Bowling. The ball game. But not everyone dates all the time. Every weekend thousands of kids are turned loose on the city. They drive around, they whistle at the girls, they stop at a friend’s house. But eventually they all end up at the same place. The drive-in restaurant. The 150 hamburger joint. They come by the thousands, every weekend, to mingle, to meet friends, to seek out a good time. That this is not a good solution is evident by the police records of arrests at these places for everything from drunk and disorderly to possession of pot.

Given the opportunity, the kids are going to drink. What better place than where they can be with friends, yet be relatively safe? They are in cars. No-body can see what is going on. Besides, what if some adult does get nosey? What if the manager does come out? You just go to another drive-in. So the managers stop seeing most of it. They have to. Chase away too many, and you destroy your own business.

Narcotics, pot, is something the kids don’t bring with them. But anywhere the kids congregate in large numbers with a minimum of adult supervision, the pushers will come.

So the drive-ins are not the answer. But every weekend they are filled to overflowing. And Baltimore has more drive-ins in proportion than any large city in the country.

The third solution offered (by adults) are the numerous teen centers and church organization dances sponsored throughout the metropolitan area every weekend in every section of town. They offer low prices. Except that they operate on the teeny bopper level. (A teeny hopper is a very young teenager — 13, 14, 15, even younger in some parts of town — who isn’t old enough to drive.) In addition, the dances do not as a rule have live music. And they are big and well-chaperoned. No teenager over 16 would be caught dead at one.

It would mean social crucifixion.

There are other discotheques in the Baltimore area. There is one in Glen Burnie, but the kids in Towson don’t want to go to Glen Burnie to dance. The kids in Parkville don’t want to go to Pikesville to dance. No one wants to go to another section of town. Somebody else’s section, where they definitely are not welcome. They go downtown because downtown is no man’s land. But downtown has nothing to offer.

Arthur Peyton’s solution? He’d like to see more teenage places open downtown. Preferably right on his own block. “I’ve even thought about opening my own competition,” he says, “but so far I haven’t had the time or money. I’m not worried about the Bluesette. As long as the kids keep coming downtown, I’ll get my share of the business.”

Actually Peyton would like to see the two or three blocks north and south of him go predominantly teenage. To turn into something that would rival the hippest sections in the hippest towns in the country. Peyton, first and foremost a businessman, might very well pull it off. “Running a discotheque is like any other business,” he says. “You have to give the customer what he wants. You have to do it at his price, and you have to stay on top of what’s happening.”

To stay on top, Peyton travels around the country, visiting discos and other teen places. Finding out what is new. What is coming. This research helps explain how he has managed to do the seemingly impossible: he has remained a part of the younger generation, at the same time making use of the knowledge that comes with business experience. He is the gorgon, the two-headed monster, the young idealist with the calculating mind of the capitalist.

This is the staff of the Bluesette, and that's Arthur Peyton, the owner, in the chair. Behind him, from the left: Eddy Magin, Dave Bernstein, Margaret Bennett, Sue Reedy.

A disco must be more than a place to go, though. It has to be a place that satisfies a sociological need. A place where adults can’t go. Where they are refused admission. Where the teenager is alone with the teenager. An escape from reality. An emotional release. A chance to get legally “high” for a few hours. To run away from home for the night. To forget that you just put in a week at school, and that there is another week in front of you, and so on for what seems like infinity.

The “total environment, total involvement” setting assaults the senses so strongly that it is comparable to being “tripped out” on some drug. But this is a drug that leaves no after effect. You are still in condition to drive home. There is no chance of death from an overdose. After it is all over, after you have been emotionally and physically drained, you step out into the coolness of Charles Street at night. It is all a rather pleasant and vague memory of unreality. It has been a place to go.

(Editor’s note: Eirik Blom, the author of this article, passed away in 2002 at the age of 55 from colon cancer. His obituary, posted at The Baltimore Sun, states that he became “a noted ornithologist and widely published authority on the world of birds.”

Special thanks to Don Lehnhoff where I discovered this article originally posted on his B’Jam blog – the article is available in PDF format at his site.

Special thanks also to Sharon Bernstein Peyton and her Bluesette Teen Discotheque Facebook page.

1967-1968 at the Bluesette was some of the best memories I have of downtown. I will never forget the strobe lights, small round tables, one bathroom for all and the movie projector movies on the wall of bubbles and paint etc.

Joe Ladd

I played keyboard and guitar for the Uncertain Things with Kathy McCabe, Bruce

Aist (sp.?), Jim Tice, Pete Plamondon and Jerry Nitzberg in 1968-1969. Shoot me an email. I’d love to hear from my old friends.

I spent every Friday Saturday (night) and Sunday Afternoon (Ron Price) at The Bluesette. Got to know some of the bands and photographed many of them at that time. I was also photographing emerging name bands such as Frank Zappa & The Mothers of Invention (Eastern HS auditorium lmao) The WHO and Jimi Hendrix. After a stint in the service I returned in late 1969 and photographed the Rolling Stones (10 Days before Altamont) and in December ,

a show with Janis Joplin, Joe Cocker and The Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

I cut my photographic teeth with bands at The Bluesette. It was a place and time I would not trade for anything.

Stopped photographing major rock acts in 1973 when it became a business and all the fun had gone out of it.

My love for music has lasted a lifetime.

Hey John ! Terrence here, you may not remember me but I,m still in touch with Henry Jonson, Fred Tepper and some other Bluesetters. Get in touch.

I spent time 1969-1970 there . I was a singer . Once I recall the band playing allowed me to jam with them .

Hey Folks

During the Bluesette era, there were several teen nightclubs in the Charles Village area. They were,,,,

Bluesette

Nut House (Ball n’ Chain)

Clark Street Garage

There was a fourth one. What was its name? I thinking “Jiminy Cricket maybe?

Anyone know?

The Blusette was the place where myself ,Sherman,Dianna,and the rest of our droup from Govanstown,Lauraville,Towson hung out every weekend ,I rem. join up $2.00 and $2.00 to enter 8:00pm to 12:00 wow what a blast and during the spring and summer all day Sunday battle of the bands ,sometimes a free concert over in Wymans park yeah . Well we all grew up most of us finished college and moved on .