by Lisa Greenhouse

Spiro T. Agnew seems to be rattling around in the collective unconscious lately, like a repellent archetype we thought we had buried long ago but that is suddenly resurrected as relevant. And in a sad commentary on our times, Agnew is once again relevant with two new books that cover aspects of his infamous career. Rachel Maddow and Michael Yarvitz’s Bag Man: The Wild Crimes, Audacious Cover Up & Spectacular Downfall of a Brazen Crook in the White House (Crown, 2020) and Charles J. Holden, Zach Messitte, and Jerald Podair’s Republican Populist: Spiro Agnew and the Origins of Donald Trump’s America (UVA Press, 2019).

Of the two books, the latter is ultimately more meaningful, though Bag Man makes for a quick and gripping read. We may remember that Agnew pleaded nolo contendere to a tax evasion charge as part of a plea bargain that required his resignation from the Vice Presidency. What we maybe don’t remember is that the income that went unreported to the IRS came from extortion. Agnew shook down Maryland engineering firms who wanted government contracts from his position as County Executive of Baltimore County through the Maryland Governorship all the way into the White House. And what was he doing with the money he acquired in this manner? He was using it to support a mistress, although that part didn’t make it into the DOJ’s report or into the press coverage. It was a gentler time.

The plea bargain only required that Agnew cop to the tax crime, really a minor part of the overall corruption. The Justice Department needed him out of office and quick. The Watergate Special Prosecutor and congressional committees were bearing down on Nixon’s separate and unrelated crimes. If Nixon were to resign or be removed from office, as things stood Agnew would ascend to the Presidency. Nobody in the Administration wanted this outcome, least of all Attorney General Richardson, who considered Agnew unfit.

Even Nixon saw Agnew as unfit for high office and according to both books, dreaded meetings with him and spent quite a lot of time strategizing with aides on how to sideline the lightweight Vice. Nixon sent him on a World tour, at one point, to strengthen Agnew’s foreign policy chops as well as to rid himself of the irritation of his presence (and then complained that Agnew spent an inordinate amount of time on the tour playing golf).

Why are we remembering this now? Golf? Financial criminals in high office? What does that have to do with the present moment? Two words: Donald Trump. Trump’s crimes are more complicated and harder to trace given their international nature and the high-powered attorneys and fixers he’s employed to protect himself. Agnew’s crimes, in contrast, were local, straightforward, and not very cleverly disguised. But as much as Bag Man is relevant, it is one-dimensional compared to the Holden et al. book’s effort to comprehend Agnew’s meaning for us almost 50 years later.

Co-authored by a trio of political scientists, Republican Populist examines Agnew, beyond his criminality (and incessant golfing), as a Trump precedent in another more significant way. Agnew took up the mantle of a right-wing populism that arose in the post-WWII era in response to multiple societal transformations such as a new working-class economic security, the Civil Right Movement, and various internal migrations of Americans, including mass suburbanization. A cultural rather than an economic populism, right-wing populism defined itself in contrast to perceived cultural elites rather than against the “economic royalists” that FDR had earlier skewered.

As pocketbook issues became less pressing in the post-war prosperity, working-class resentments refocused from economic actors onto college administrators who indulged longhaired war protestors and onto those who would remove prayer from public schools. Their sense of grievance encompassed those who suggested that tight-knit ethnic neighborhoods or the new suburban developments be racially integrated and especially liberal intellectuals who seemed to imply that people were bigots and intolerants if they objected to these measures.

A vote for Agnew is a vote for good government!

Since the 1920s, several internal migrations contributed to the eventual rise of cultural populism. Midwestern Protestants, largely socially conservative and evangelical, streamed to the American Southwest to take jobs in aerospace and other industries. There they began to organize politically.

In addition, after WWII masses of white people — the definition of white having expanded to embrace Eastern and Southern European immigrants — taking advantage of newly available fixed-rate, long-term mortgages and GI subsidies, decamped for the suburbs. But their new backyard barbecue and Kiwanis Club lifestyle seemed precarious. Southern blacks continued to pour into overcrowded Northern ghettos. Ethnics in the Northern metropolises jealously guarded their recently attained status and prosperity against the possibility of reduced social stature and home values as integration of the newly arrived blacks began to be contemplated.

The Northern, ethnic working class, Levittown suburbanites, and Southwestern evangelicals were all susceptible to the new form of populism that was the in air and that was beginning to find a niche in the Republican Party. Agnew embodied many of the Republican Party’s new constituencies. He was the son of a Greek immigrant to Baltimore. He fought in WWII and then made the trek out of the city to a new, detached house in the Baltimore County suburbs. This was the immigrant family’s prototypical second-generation quest for assimilation. Agnew deemphasized his ethnic roots. He went by Ted.

Deprived by Nixon of a policy role in the White House, Ted spent most of his time planting the Republican seed in another fertile region of the country: the South. Southerners had been trickling into the Republican Party since Truman integrated the Armed Services and the Federal workforce. Agnew revved up the process through a series of speeches and campaign events in which, using his Trumpian gift for riling up a crowd by slinging insults, he implemented the Republican Party’s newly coined “Southern Strategy.”

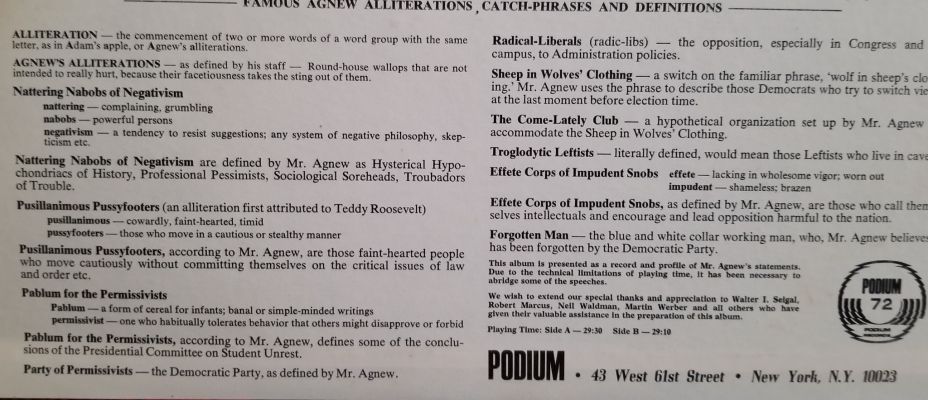

Agnew was famous for the alliterative taunt: “nattering nabobs of negativism” and “hopeless, hysterical, hypochondriacs of history.” Agnew pilloried college students and professors, Federal bureaucrats, and journalists from the major networks as well as from the national newspapers. During the 1968 election season he called a Baltimore Sun reporter a “fat Jap.”

The Speeches That Stirred America: Agnew’s Greatest Hits!

In speeches drafted by Pat Buchanan and William Safire in which Agnew added the finishing touches, the Vice President anticipated Trump’s content as well as his combative style. What neither book points out explicitly is that Agnew also previewed the current role played by conservatives in Government. Not prohibited from policymaking as Agnew was by Nixon but simply uninterested in the nuts and bolts of governing, politicians like Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, Matt Gaetz, and Donald Trump, use their public positions to garner media attention through provocative culture war rhetoric and stunts. They are entertainers above all else and in this way, have much in common with the Agnew prototype.

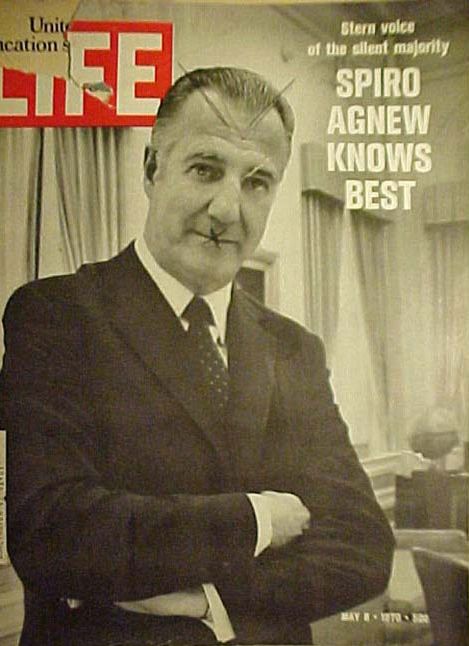

Media star Agnew was a populist hero to many

Before Nixon soured on Agnew, he was very much attracted to him. During the fateful campaign year of 1968, Governor Agnew of Maryland came to Nixon’s attention when, in the aftermath of the King riots, he dressed down a group of moderate Baltimore civil rights leaders before the TV cameras. Nixon needed to find a running mate who while acceptable to liberal Rockefeller Republicans in the Northeast would also not repel the crucial Southern votes he needed to win (George Wallace had entered the race as an independent which complicated Nixon’s position in the South).

Agnew seemed to fit the bill. He had an established record of supporting local civil rights initiatives such as the integration of the Gwynns Falls Amusement Park yet had little tolerance for the movement’s turn toward militancy or its new focus on economic redistribution. Remember that Martin Luther King had immersed himself in the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968. He was in Memphis to support striking sanitation workers when he was assassinated. Agnew’s support for civil rights had reached a tipping point when Pat Buchannan directed Nixon’s attention to the Governor’s speech before the dismayed Baltimore civil rights leaders, most of whom walked out as Agnew harangued them.

Most of these black leaders had voted for Agnew. The 1966 Governor’s race had pitted him against George Mahoney, a Democrat whose racist slogan, in the face of pending fair housing legislation, was “Your Home is Your Castle. Protect it.” The black leaders felt betrayed. Nixon felt like maybe he had found his man.

The problem with Agnew was that he didn’t know anything about Federal policy or Government. As recently as 1966, he had been Baltimore County Executive and now, in 1969 he was the person next in line for the Presidency. Agnew was good, however, at delivering culture war attacks and in doing so he developed a MAGA-like constituency of his own, to the point where he became indispensable. Nixon couldn’t dump him without offending an important voting bloc. That is Nixon couldn’t dump him until Watergate changed the political calculus.

Agnew ultimately dumped himself from Nixon’s favor

(“Agnew Drops the Bomb” illustration by Robert Soulsby)

Agnew’s post-political career involved golfing with and borrowing money from his pal, Frank Sinatra, relying on the international connections he made as Vice President, mostly with dictators and juntas, to arrange business deals for clients, writing a political thriller and (intended to be exculpatory) memoir, and in the words of Maddow and Yarvitz, “market[ing] himself internationally as an influential American anti-Semite for hire.” He was successfully sued by taxpayers in Maryland for the amount of the extorted money plus interest and in desperation offered his services to the Saudi Arabian Crown Prince. In a letter to the Crown Prince which Maddow and Yarvitz found in the Spiro Agnew Papers at UMD, Agnew offered to mount a “fight against the Zionist enemies” if the Prince would help him by funneling two million dollars into a Swiss bank account. The authors of Republican Populist do say that Agnew fought honorably in WWII. So there’s that. 🙂