By Michael Anft, Photos by Steven Brown (Baltimore City Paper, 2/16/1990)

David B. Irwin had just formed his own law firm with four associates. His library wasn’t yet stocked and furniture was still being moved in when his firm’s first client, referred by another lawyer, made his way through the door. Even if Santo Victor Rigatuso hadn’t been Irwin’s first client in October 1988, Irwin says he would have no trouble remembering him. “I’ll never forget him sitting in my library,” Irwin says. “He’s an interesting-looking person. He was wearing a floppy, cowboy-type hat pulled down over curly black hair and sunglasses. He had quite a presence about him.”

Rigatuso, known to Irwin at the time as Bob Harris (the most-used of his dozen or so aliases), had reached TV viewers across the country with his Santo Gold and Forever Gold promotions, which ran on over 100 channels nationwide from 1982 to 1986. Seizing upon mail order and TV ads as a way to get rich, Rigatuso, a former barber and music shop owner, concocted schemes for selling jewelry and credit cards that netted him millions of dollars.

“He’s got more ideas and energy than anyone I’ve ever met,” says Irwin.

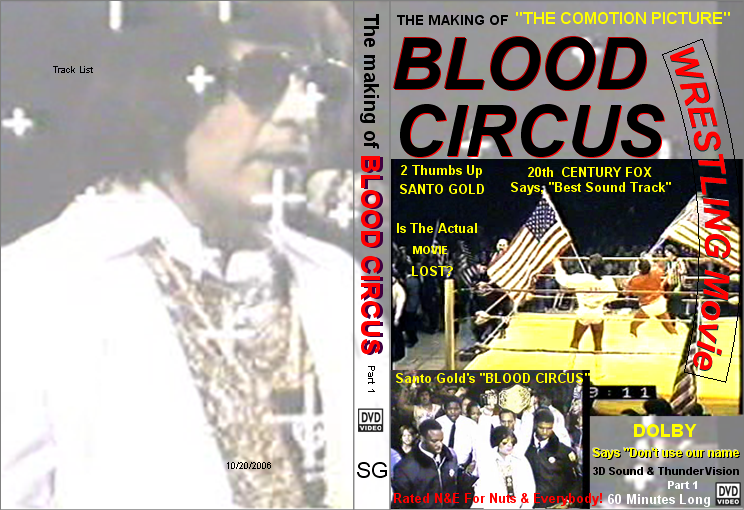

Besides his various retail ploys, Rigatuso (again under the name of Bob Harris) found the time to produce, write, and star in his own, self-proclaimed “vanity film,” Blood Circus, which was billed as “the atomic wrestling movie.”

Santo Rigatuso is a ninth-grade dropout who grew up in working-class Pigtown and achieved wealth in spite of social problems brought on by episodes of Tourette Syndrome, a neurological disorder characterized by nervous tics and involuntary, inappropriate utterances. Evidence offered in some of his court cases points to Rigatuso as a man who purportedly lived the American Dream, but his story isn’t exactly the stuff of a Horatio Alger novel. According to those who followed his rise and fall, Rigatuso’s business ingenuity, like much of his merchandise, was a sham.

“What you have [in Rigatuso] is a guy, who has basically changed his name and those of his companies, even though they were all doing the same thing—defrauding the public,” says Fred Addison, a postal inspector in Virginia. The aliases, Addison contends, were a way for Rigatuso “to stay one step ahead of the authorities.”

Roger Wolf, a special prosecutor for the Maryland Attorney General’s Consumer Protection Division (CPD), adds that Rigatuso had a way of fending off consumer complaints. “It was a new corporation almost every week,” he says. “As some complaint would develop against one [corporation] he would change its name and slightly change his solicitation letters.”

In 1982 Rigatuso received the first of four cease-and-desist orders from the U.S. Postal Service, which were aimed at forcing Rigatuso to abide by postal regulations. By 1984 Rigatuso had become a regular subject of consumer-beware pieces on local TV newsshows. But despite all the attention Rigatuso’s schemes grew more grandiose. “As time progressed,” says Dick Irby, former consumer reporter for WMAR-TV, “[Rigatuso] just seemed to get bolder and bolder.”

The state began focusing attention on Rigatuso in 1985, at which time he was forced to make restitution to consumers, as well as cease marketing his Santo Gold jewelry via mail. “I don’t think he paid back the consumers,” the CPD’s Wolf says, “although he was supposed to.” In November 1988 a U.S. District Court judge held Rigatuso in contempt of court and ordered him to jail for failure to turn over complete records of his Credit Card Authorization Center Inc. (CCAC). The case was instigated by postal inspectors, who found that CCAC’s promises to help clients obtain major credit cards, such as MasterCard and Visa—for a fee ranging from $15 to $49.95—were fraudulent. Some of the people who paid the fee instead received two paper cards, “The National City Card” and “The Gold Card 2500,” which could be used only to buy goods from Rigatuso’s catalogs of jewelry and refurbished furniture items. Others who paid the fee received nothing, it was alleged. Rigatuso spent 10 days in jail on the contempt charge, and his assets were seized. (They are currently thing held in receivership in New Jersey).

The state began focusing attention on Rigatuso in 1985, at which time he was forced to make restitution to consumers, as well as cease marketing his Santo Gold jewelry via mail. “I don’t think he paid back the consumers,” the CPD’s Wolf says, “although he was supposed to.” In November 1988 a U.S. District Court judge held Rigatuso in contempt of court and ordered him to jail for failure to turn over complete records of his Credit Card Authorization Center Inc. (CCAC). The case was instigated by postal inspectors, who found that CCAC’s promises to help clients obtain major credit cards, such as MasterCard and Visa—for a fee ranging from $15 to $49.95—were fraudulent. Some of the people who paid the fee instead received two paper cards, “The National City Card” and “The Gold Card 2500,” which could be used only to buy goods from Rigatuso’s catalogs of jewelry and refurbished furniture items. Others who paid the fee received nothing, it was alleged. Rigatuso spent 10 days in jail on the contempt charge, and his assets were seized. (They are currently thing held in receivership in New Jersey).

Last summer Rigatuso was ordered to pay $2 minion in restitution by the head of CPD. The state alleges that Rigatuso was fraudulent in promoting three schemes: Santo Gold, a “millionaire giveaway,” and the credit card operation.

In November 1989 Rigatuso pleaded guilty, on the advice of Irwin, to mail fraud and tax evasion charges in Baltimore. U.S. District Court Judge Joseph Howard sentenced Rigatuso to 10 months in a federal prison camp in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Howard also ordered Rigatuso to pay $106,000 in restitution to the 5194 customers who were bilked in the credit card scheme. Rigatuso began his sentence this past January.

But although Rigatuso is currently in jail, he’s not out of business. According to published reports, his U.S. Credit Corporation of America Inc. may have as many as 100,000 members in its buyers’ club. Even though U.S. Credit’s mailout bluntly states, “This is not a solicitation for Visa or MasterCard,” the postal service still regularly receives complaints about the company. “We have several hundred complaints against U.S. Credit dating back to May 1989,” says Doug Turner, a postal inspector in Washington, D.C. Wolf adds that the state CPD is also receiving regular complaints concerning U.S. Credit. “[U.S. Credit] is a different corporation started with different people,” says Wolf, “but as far as I’m concerned, it is an extension [of CCAC]. If U.S. Credit is willfully fraudulent and follows the same pattern of abuse [as Rigatuso’s previous corporations], we’ll urge a prosecutor to take the case.”

Inauspicious Beginnings

Rigatuso’s story—a script seemingly written for the greed-first 1980s—began 43 years ago. Born to a stable Pigtown family and raised in the 1200 block of W. Cross Street, Rigatuso (who, like most of his family, declined to be interviewed for this article) dropped out of Edmondson High School at age 16 and took over the generations-old family barber shop on Washington Boulevard upon the death of his father. Ending his formal education apparently wasn’t a difficult decision for him.

“He was terribly tortured in school because of his nervous tics and the inappropriate sounds that come out of the typical Tourette Syndrome victim,” says attorney Irwin, who made Rigatuso’s condition and mental health an issue during his federal trial. “He’s incredibly scarred by it.”

A long-time neighbor, Gladys Poke, says she remembers the Rigatuso family as “a very nice one” composed of three sons and one daughter. “They were all nice kids. Some would come over to my house and say, ‘I wish I could do that’ or ‘I wish I could do this.’ Their father apparently was very strict.” A relative who asks not to be named adds that Rigatuso developed a propensity for entrepreneurship at a very early age. “Even when he was a teenager,” the relative says, “he had his schemes for making money. That’s certainly always been the case with him.” Adds a Rigatuso acquaintance who requested anonymity, “He was always selling something. He worked at one of the [city-owned] markets. He was always on the shill and had some very big ideas.”

Earl Riddle, another neighbor who remembers the young Rigatuso, says, “He was a very good barber who would talk to you about most anything. He was just a regular guy who ran a barber shop.”

In a previously published interview, Rigatuso claimed he eventually turned the barber shop into Santo’s Music Store. Later, he married, moved to Florida, and returned to the Baltimore area in 1980. Other information about his past, both here and in Florida, is difficult to glean. “He’s very secretive about his family,” says the acquaintance.

Home Again

Joe Czernikowski remembers taking care of customers at the Dundalk restaurant he managed in 1982 when, by chance, he encountered Santo Rigatuso. Czernikowski even remembers the date. “I met him on March 1, 1982—on his birthday,” he says. “He had his whole family there celebrating: his wife, his two brothers, their wives, his mother, and his two children.” (Rigatuso now has three children.)

Since the restaurant was being readied for auction, Czernikowski was worried about his future. “I knew I was going to need a job,” he says. Enter Rigatuso. “He seemed like a very likable guy,” Czernikowski says. “He was talking about how he was going to need some help with this new business. Up until then he and his brother said they were working in advertising. I spoke up, and I was working with him later in the month.”

Czernikowski served as a media buyer for Rigatuso in an office in Bowie. The first product Rigatuso sold—through corporations known variously as San, Inc., Mid-Atlantic Distributing Company, and J KJ Enterprises—was a musical watch that played the tune of “The Yellow Rose of Texas,” Czernikowski recalls. According to postal service records, complaints about JKJ Enterprises first reached post offices in 1981. “The deal was you’d get a man’s watch and a woman’s watch for $39.95,” Czernikowski says. “The man’s watch would play [the song], but the woman’s wouldn’t [by design].”

Czernikowski would book ad time through TV stations nationwide, he says. “We would pay according to how many households a station was pulling in,” he explains. “We usually paid $200 to S1500 per spot. Out of the 900 stations across the country, we probably advertised on over 100 in all, at about 30 to 40 [spots] per week.” After Rigatuso sold out of “The Yellow Rose of Texas” watches, Czernikowski says, he started selling Santo Gold. “I think the first thing we sold [through Santo Gold] was an 11-piece chain set, which went for $I9.95”

In a 1987 interview Rigatuso said he developed the trademarked Santo Gold process for goldplating in 1982. The process was described in a letter mailed out to purchasers of Santo Gold bracelets: “First, quality steel wire is cut and faceted into individual links, over one hundred in all. Next, these links are wound and formed into an interlocking bracelet. Each link is cut by skilled craftsmen. A jump ring and fold over latch are then attached by hand. The wire bracelets are then treated with Santo Gold’s secret patented formula. Finally, real 24-karat gold is electrostatically bonded producing a high luster coating.” This letter, partly the result of a set of charges brought against Rigatuso by the postal center, also disputed postal inspectors’ claims that Santo Gold wasn’t what it claimed to be.

But according to evidence presented in a state administrative hearing, the electroplated gold, a cheaper quality than the 24-karat variety promised in ads, was only one-fiftieth to one-one hundredth of an inch thick. Almost immediately after Rigatuso (also named in some documents as Joey Sew) began advertising Santo Gold in late 1982, postal authorities began receiving complaints about the jewelry’s quality, about a lack of promised refunds, and about the business’ methods, which included mailing COD packages to people who had never ordered any Santo Gold products. “People either didn’t get what they ordered,” adds Roger Wolf, “or they thought the merchandise was trashy.”

Despite all the regulatory attention, Santo Gold’s TV ads continued to promise 24-karat gold, to the point of claiming, “Santo Gold is pure 24-karat gold from the gold bullion. No metals arc used to break down the gold karat.” Two bracelets, plus a “beautiful surprise gift” and a Santo diamond ring, sold for S19.95, plus $3 shipping and handling. Another Santo Gold TV ad, this one broadcast in 1983, offered gold chains for $29.95 with COD orders; the ad claimed that in “1982 and 1983 combined, over 40 million chains will be purchased by Macho Man and Ms. Woman.”

But these unsolicited COD schemes eventually backfired. In November of 1984, San, Inc.’s mail order house made the mistake of unwittingly mailing a COD package stamped, “You ordered this from T.V.” to the postal inspector in Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania, thus spearheading another postal service action against San, Inc. Like the Pennsylvania postal inspector, many others complained to local post offices about being sent goods they didn’t order and being charged $25.74 on delivery.

According to Czernikowski, Rigatuso’s mail-order scams were so slick that his employees never knew about his schemes’ real purpose. “I never knew anything about what was going on until much later,” Czernikowski says. ‘”We’d get TV stations asking us about certain coupons we sent to people when we ran out of merchandise, but I never heard anything about [charges of fraud] on my end.”

Furthermore, Czernikowski claims, Rigatuso looked after his workers like a caring father. “Whenever people had problems,” he says, “[Rigatuso] would take them into his office and talk with them for a couple of hours. And when I was in the hospital for a month, he made it a point to bring me a paycheck every week. If any of us got into financial trouble, he’d offer to help us out. He’d even let some of the employees, different girls, wear pieces of the jewelry around the office.”

Others who know Rigatuso also emphasize this softer side of his personality. “He had a habit of taking people on who had problems,” the anonymous acquaintance says, “and he could never fire anybody. He was too nice a guy.”

Regardless, three postal service cease-and-desist orders and mounting pressure from the-state briefly put an end to Santo Gold. In 1985 San, Inc. filed for bankruptcy. Still, using various corporate names, Rigatuso continued to sell jewelry with monikers like “Forever Gold.” According to those close to the case, Rigatuso had learned how to survive as a businessman — while under scrutiny. “In order to (get around-the 1985) cease-and-desist order,” Addison says, “he started using United Parcel Service to deliver his products.

Let the Games Begin!

Also in 1985, Rigatuso fusing the alias Bob Harris, placed ads in local newspapers and on local TV stations soliciting movie extras for what was to be his creative masterpiece, the sci-fi wrestling extravaganza Blood Circus. There was a characteristic twist. Extras who paid $9.95 to be in the film—shot at the Baltimore Arena (at that time still known as the Civic Center)—were told they would “watch.. 20 world-famous wrestlers rip each others head (sic) and arms off and throw them into the audience.”

According to published reports, 2800 people responded to the ads and showed up at the Civic Center to see the filming of Blood Circus. However, dissatisfied with the lack of action, many “extras” asked for their money back but never received it.

The 101-minute film featured American wrestlers taking on invaders from the USSR and Outer Space in a place called “Santoville Earth.” The plot took many detours, including sales pitches for Santo Gold products. Featuring local sports personality Charlie Eckman as the ringside announcer, the movie also promised viewers “scream machines,” something called “Thunder Vision.” and “angels that bother everybody.” Lou Cedrone of The Evening Sun dubbed the plot “incomprehensible,” but then went on to laud the clarity of the photography and the film’s classical score, as well as the acting appearances by members of Rigatuso’s family.

In a 1987 newspaper interview, Rigatuso (as Bob Harris) said he didn’t worry about plot continuity. “The film won’t make sense,” he told a reporter. “It will just make dollars.” But in November 1987, unable to find a distributor who would handle the film, Rigatuso rented four local theaters for Blood Circus‘ belated premier. According to one newspaper account, three people showed up at the opening at the Patterson Theatre in Highlandtown—two movie critics and one extra. Rigatuao claimed that his combination of wrestling and science fiction would take the world by storm, but the atomic wrestling movie just bombed.

Despite the film’s financial failure—Rigatuso claimed the film’s price tag was in the millions—those who have known Rigatuso say the movie was tragic for other reasons. “What you have in Blood Circus,” says attorney David Irwin, “is a man totally out of control.”

Rigatuso played “rock star” Santo Gold in one five-minute segment of the film, singing a video of sorts about his products. In one review of the film, a critic noted that “[Rigatuso] dresses like a late-career Elvis and moves like a tired John Travolta.” But Irwin says that the Santo Gold character was an indication of the mental illnesses Rigatuso had been experiencing since he was young. “He’s literally an insecure, scared little boy with serious mental problems,” Irwin says. “Like a lot of little boys, he acts out flamboyantly as a defense. Blood Circus made all that very public.”

Rigatuso played “rock star” Santo Gold in one five-minute segment of the film, singing a video of sorts about his products. In one review of the film, a critic noted that “[Rigatuso] dresses like a late-career Elvis and moves like a tired John Travolta.” But Irwin says that the Santo Gold character was an indication of the mental illnesses Rigatuso had been experiencing since he was young. “He’s literally an insecure, scared little boy with serious mental problems,” Irwin says. “Like a lot of little boys, he acts out flamboyantly as a defense. Blood Circus made all that very public.”

Despite his problems, Rigatuso’s enterprising spirit never flagged. In addition to hawking his film, he also opened a 976 pay-per-listen phone line promising to treat callers to the “bonecrushing sounds” of Blood Circus for $2. And at the time the movie made its debut, Rigatuso was involved in another scheme: distributing the supposed wealth of an unnamed millionaire who had died recently, leaving $2000 blocks of his $7 million fortune to anyone who would pay a $2 phone processing charge and a $50 handling fee. “There was no millionaire,” Wolf says, adding that the merchandise sent out to consumers “was the same old junk.”

Free Money

In February 1988 Rigatuso (still using the name Bob Harris) came up with his ultimate moneymaking scheme. According to documents filed in U.S. District Court by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Baltimore, on February 12 Rigatuso used an in-house list of 1000 of his old jewelry customers to test mail solicitations for a new credit card company, CCAC. The test mailing stated, in part, “Your charge limit has been approved for $2500…. We handle thousands of transactions per year with Visa, MasterCard, American Express, Carte Blanche, Gold Card, National City, etc.” A detachable order form at the bottom of the letter read, ” CCAC guarantees that you will receive a minimum of two charge cards” for an initial service charge of $15.

According to those same documents, the test mailing was “unusually successful,” leading Rigatuso to begin larger mailings across the country. Rigatuso had initially made efforts to obtain permission to sell nationally-recognized credit cards, but was successful, the documents note. Although an attorney retained by Rigatuso only eliminated Carte Blanche and American Express from the list of credit cards in his later mailings—saying, the federal government later maintained, that he had made arrangements with a bank to issue Visa and MasterCard.

Even though he never entered into such an agreement, Rigatuso hired Associated Computer Services (ASC) in Springfield, Virginia to mass-mail 140,000 letters in March and April 1988. After ASC received inquiries about CCAC mailings, they changed the return address on the mailout to a CCAC address in Bowie. Rigatuso opened other post office boxes in Hanover and Annapolis to handle the large response.

By late April, postal inspector Fred Addison recalls, he was swamped with complaints. “I started receiving complaints at least every day and sometimes 20 to 25 per day,” he says. “Toward the end of the case, in my office alone were in excess of 5000 complaints, which is highly unusual for a mail fraud case. Usually, we’ll get around 100 complaints total.” Addison, a postal inspector for 12 years, says, “I’ve never seen anything like this before.” Foremost among the complaints, Addison says, were bait-and-switch charges. “People weren’t receiving the cards they thought they’d receive,” he says, “and a lot of them weren’t getting any satisfaction through refunds.”

One office employee of Rigatuso’s, who wishes to remain unidentified, claims that Rigatuso’s refund policy was always under-handed. The employee, who worked for Rigatuso from 1986 to 1988, says, “I presented to him that we were having problems with refunds. His quote was, ‘As long as I mail out one refund per day, everything will be fine’ ” The employee claims that although Rigatuso had a very friendly side, he would also dream up gimmicks that were obviously designed to defraud. “When he was selling jewelry (during the millionaire scam),” the employee says, “he talked about painting bricks gold and putting them in packages to give them weight. And we always had problems with bills. He would tell us to send unsigned checks [to stave off, creditors].”

Although Czernikowski claims he saw nothing mentally wrong with Rigatuso, the anonymous employee states that he was subject “to wild mood swings. Sometimes, he’d sit in his office in the dark. At other times he was bouncing off the walls.” His ever-changing moods affected the way he conducted business, the employee claims. “From the time that I went to work for him, there were many times when he felt he was doing things the right way. But at other times he would have a mean streak, like with the bricks and the bills. It was like he was more than one person.”

After signing an interim consent agreement with the postal service to clarify his mailout’s sales pitch in late April 1988, the government contended, Rigatuso’s dealings took a turn for the worse. Although he rephrased his solicitation letters at that time to state that customers would receive only credit cards good for Rigatuso’s catalogs, he raised his processing fee to $49.95 for “a lifetime membership.” Also, the letters continued to make claims that CCAC could help customers obtain national credit cards. From April to September a New Jersey company mailed out millions of letters to prospective CCAC customers. Meanwhile, Rigatuso persistently called an executive at Key Federal Savings Bank in Randallstown, documents allege, in hopes of getting clearance to issue major credit cards. No permission was forthcoming. From August 1988 to February 1989 the state Attorney General’s Office claims, CCAC received 3000 checks per day and a total of about $10 million.

In September 1988, when postal inspectors confiscated two truckloads of records from CCAC’s new office at a former bingo palace in Gambrills, Czernikowski noticed a change in Rigatuso’s behavior. “He started getting very nervous after that, even though he told us not to worry about it,” Czernikowski says. But Czernikowski worried. “It was the first I’d heard of any wrongdoing,” he says, adding he left CCAC shortly after the postal raid. “I couldn’t believe it, but I didn’t want to work at a place that was under investigation.”

Roger Wolf says that testimony in the CPU’s case showed that most of Rigatuso’s employees were not suspicious of his methods. “A lot of people thought that [Rigatuso] was a decent guy,” Wolf says, “that he just went to excess at times. They didn’t think that anything he did was intentional. A lot of his employees were not upset with him. It was only at the end that they began to realize what a scam it was.”

In the course of looking through the Gambrills warehouse, Addison states, investigators noticed that many of the goods listed in CCAC’s catalogs weren’t present. “We found one broken answering machine and no TVs,” he says. “The stuff he advertised just wasn’t there.” In late September 1988, a New Jersey judge shut CCAC down, calling the firm and its methods “despicable.”

In July 1989 at a CPD hearing in Baltimore, Rigatuso was ordered to pay $50,000 in restitution but was found not guilty of intentional fraud. Upon subsequent review of the case, which is currently in a lengthy, ongoing appeals process, the restitution amount was raised to $2 million.

Temporarily, at least, Rigatuso’s credit card scheme was finished. And there were still 12 federal criminal charges to face.

Bananas?

Events at a federal grand jury hearing earlier in 1989 convinced David Irwin that Rigatuso may not have been competent to aid in his own defense. “He disregarded my advice and the advice of three other attorneys and testified in front of the grand jury,” Irwin says, adding that Rigatuso hardly helped his own case. “He offered [U.S. deputy prosecutor Gary Jordan] a banana [during grand jury proceedings.] There wasn’t anything derogatory about it. [Rigatuso] just does inappropriate things.”

Rigatuso's Attorney, David Irwin. "He's (Rigatuso) a very, very nice guy. He just does inappropriate things."

During thc competency hearing that preceded Rigatuso’s trial, Irwin ticked off some of those “inappropriate” things. “He’s on a non-meat diet, mostly fruit,” Irwin explains now. “He has to eat every couple of hours, so during the grand jury hearing he brought bananas to keep going. And he’s a very, very nice guy. He’d offer you the shirt off his back, literally. So, he offered [Jordan] a banana. He does inappropriate things, which tends to be a problem [for his lawyers].”

During the competency hearing, Rigatuso’s psychiatric past was brought to light. A psychiatrist explained that Rigatuso was under medication for a manic-depressive disorder, that his family was in therapy to help him, and that Rigatuso suffers from delusions of grandeur. “I wasn’t going to plead him guilty until he was found competent [to stand trial],” Irwin says.

But Judge Joseph Howard noticed that Rigatuso made frequent comments to Irwin during proceedings, an indication that he was aware of his predicament. “It was an ironic twist in that I was hearing too many ideas [from Rigatuso on his defense],” Irwin says. “He wasn’t helping me because he had too many ideas, as opposed to the client who doesn’t help at all.” Ultimately, Howard found Rigatuso competent to stand trial.

Although Rigatuso had claimed some degree of innocence privately, Irwin had him plead guilty to mail fraud and tax evasion charges. “I would never plead a client guilty who didn’t think he was guilty,” Irwin says. “He has lots of explanations that come close to saying he’s not guilty, but the point that I tried to make clear to him was that he knowingly mailed out that [credit card] solicitation. He admitted that in court.”

Howard sentenced Rigatuso to concurrent 10-month jail terms on both counts, saying that the case’s scope cried out for a prison sentence. “It was a godsend that he only got 10 months,” Irwin says. “The government was trying to get him 28 months.” During his final arguments, Irwin made one last plea for probation. “I said [Rigatuso] has an incredible talent for making money,” Irwin remembers. “I put that in the context of [keeping Rigatuso out of jail so he could make] restitution.” Another Rigatuso attorney has filed a post-sentencing motion asking Howard to reduce Rigatuso’s prison camp term at Lewisburg, citing his mental health and his family.

Minding Business

Even as various legal proceedings were taking place, U.S. Credit Corporation of America, begun by Rigatuso and three partners in May of last year, was doing a booming business. (According to a report published in late 1989, U.S. Credit may have as many as 100,000 members in it buyers’ club.) To insure that he didn’t make the same mistakes with U.S. Credit as he had with CCAC, in late 1988 Rigatuso had hired Sheldon Lustigman, a New York attorney who specializes in postal regulation matters.

“I saw there was room for improvement,” Lustigman says of the CCAC mailout. Lustigman advised Rigatuso to include a disclaimer concerning delivery of major credit cards in U.S. Credit’s literature. “We’re not interested in making people unhappy or dissatisfied,” Lustigman says. “A lot of people can buy merchandise on credit who otherwise couldn’t through this program, which is clearly and fairly stated [in the company’s literature].”

Although the state and postal inspectors have received complaints about U.S. Credit—and although Addison claims that “[Rigatuso] still isn’t delivering what he says he’ll deliver”— Lustigman’s advice may ultimately save Rigatuso from future litigation. Doug Turner concedes that while the postal service has received numerous complaints about U.S. Credit, inspectors’ hands are tied. “The difference is [Rigatuso is] complying with the [April 1988] consent agreement,” says D.C. postal inspector Doug Turner. “He’s telling people that they have credit for his catalogs. Many of the complainants writing in tell us that they’re disappointed in not receiving real credit cards, but if [U.S. Credit] abides by the consent agreement, then I really don’t have much of a case.”

Rigatuso’s marketing efforts obviously haven’t been curtailed by his incarceration. But Irwin says no one connected with Rigatuso takes any consolation in that. “This case is a tragedy,” he says. “[Rigatuso] is a sweet guy. He’s the kind of guy who genuinely loves his kids. In his grandiosity, he can be an incredible wheeler-dealer with all the [traits] of Santo Gold in Blood Circus. But whether that’s him, I don’t know…. I feel very sorry for him because he’s away from his family. That has to be torturing him.”

A spokesman at Lewisburg says that Rigatuso is working as an orderly in the prison camp’s administration building. According to Czernikowski, Rigatuso bought a home for his wife near the prison.

(Special thanks to Peter Walsh for providing Baltimore Or Less with a microfilmed copy of this article. Yes, microfilm.)

Related Links

You guys should pool all of your money together and purchase the distro rights for BLOOD CIRCUS. Make sure to get a receipt, however.

BLOOD CIRCUS is a Baltimore holy grail and I still kick myself for not going to the filming.

Nice find. I was 10 when I first started seeing his infomercials, and even then I knew it was a fraud, I don’t know how sorry I can feel for the rubes that fell for it. My favorite is the auction-like informercial you can find on YouTube, who would see that and order anything from him?

Thanks Peter Walsh – you are the gift that keeps giving! Great Mike Anft stories, great profile of a legendary “Baltimoron”!

Love the BLOOD CIRCUS Scream Bag taglines: “3D Santophonic sound! Thundervision that will shatter your seats!”

A very interesting story. I found out about him from his recent gaff with singer “Santigold”, who formerly went by Santogold, and he actually won against her in court, forcing her to change her name to the Santi version. His informericals and videos with new songs are on Youtube, and his website is selling just about every service you can imagine, along with a talent search. Completely insane! After reading this article, the pieces of the puzzle fit together.

Pingback: 21. The One Ring Circus | Hosted by Dan Delgado

Just kill yourself already, if you havent noticed. NOBODY gives a fuck

Pingback: 12 Awful Infomercial Products Millions of People Still Bought | Outdoor Techies

Pingback: 12 Awful Infomercial Products Millions of People Still Bought – IT NewsDom

Pingback: SeanPaulMurphyVille: The 10 Worst Films I Paid To See