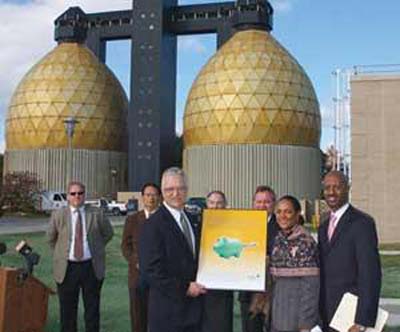

Disgraced Former Baltimore Mayor Sheila Dixon visited the shit plant before her sentencing and resignation from office.

By J.K.O’Neill (The Dundalk Eagle, 11/24/198, updated 04/03/2008)

As most people around here know, those golden, egg-shaped towers that rear in majestic, near-eldritch splendor over Eastpoint Mall, North Point Boulevard and the Beltway have something to do with the city-owned Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant, that good neighbor that has brought such joy into the lives of area residents for nearly a century.

But, prior to this week’s question, I, like many others, had no idea what these towers were supposed to do. Why they were painted gold seemed an easy question to answer. Obviously the City of Baltimore, in its infinite wisdom, wished to have a sewage treatment plant that was, on sunny days, visible from space. This was done so that passing aliens, curious as to our level of civilization, could quickly and conveniently establish that we had developed advanced technology to eliminate our elimination, and thus determine that we are not so easy to conquer. According to this plan, the aliens would then go elsewhere for easier pickings.

Thanks, Baltimore City, for preventing alien invasion and preserving life on Earth. Baltimore City, however, is too humble to acknowledge the vital role that it plays in planetary defense. For this reason, a spokesman for the city’s Department of Public Works tells a different story. He states that these towers are anaerobic digesters. As you can probably tell by this name, the rest of this story gets icky. The “eggs,” built in 1992, each hold 3 million gallons of solid and liquid waste and process this waste through, according to a DPW document, “a biological treatment where anaerobic bacteria [meaning germs that don’t need to breathe oxygen] decompose and stabilize organics [meaning that stuff you don’t mention in polite company] in thickened sludge.”

This process, which requires temperatures of 96 to 98 degrees Fahrenheit, “reduces volume of biosolids [it’s amazing how many euphemisms they can come up with for this stuff] by destroying volatile compounds while producing burnable gas as a byproduct.”

Biosolids? Burnable gas? Thickened sludge? A brief digest of how these digesters digest is hardly an aid to digestion. Fortunately for us all, especially those who work at the plant, the DPW points out that the digesters are extremely efficient because they “never need cleaning.”

The eggs are 80 feet in diameter at the base and 150 feet high. They were designed in Germany, and the egg shape assists in the process of digestion.

They digest sludge for 10 to 15 days, after which the sludge is drained to a centrifuge where water is removed. The dewatered sludge is then made into pellets or fill. The eggs are made of concrete and steel and coated in gold-painted aluminum. The aluminum helps protect the underlying structure, but, according to the DPW, the gold paint is pure window dressing.

It seems that DPW director George Balog wanted the new facility to be an attractive local landmark, so he ordered the gold paint to make the towers “glittery.” According to a department spokesman, he got the idea from Disneyland.

Anyway, the eggs are part of the overall operations at the Back River Wastewater Treatment Plant, originally opened as a state-of-the-art facility in 1911. Through the years, various methods have been used to dispose of, process or disappear the unpleasant byproducts of our biological functions. These methods have included landfill dumping, storage in open-air lagoons and transportation elsewhere (you didn’t really think I was going to get through this column without mentioning the infamous “Poo-Poo Choo-Choo” incident of 1989?).

This brings us to our second question of the week, which was so linked to the first that I figured I could address them both in a single column (this is known, professionally, as efficiency born of laziness). Jackie Nickel of Essex (editor’s note: Ms. Nickel died last year) wants to know, “What’s up with that very tall, red and white smokestack at the treatment plant?” So many questions about sewage this week. I myself belong to the flush-and-forget-it school, but it apparently takes all kinds.

OK, the 350-foot smokestack is a legacy from the facility’s environmentally unsavory practice of burning sludge. They needed a really tall tube to loft what must have been extremely nasty smoke and gasses as high up as they could, another chapter in the facility’s often ill-fated history of attempting to reduce the reek in the area. I have been assured, however, that this practice was discontinued, and the giant chimney has not been used since 1972.

So what happens to the sludge now? Do you really want to know? Much of the digested — ahem — sludge is dehydrated and pelletized for use as fertilizer. Some of the sludge is mixed with dirt for use in landfill projects. Some is sent to be composted.

And the smell? Well, an exhaustive and thoroughly scientific poll of area residents reveals that, since the construction of the golden eggs, some think it’s gotten better, some think it’s gotten worse, and some think it’s about the same. The air quality around the plant is monitored by a state agency with the truly scary name of the Air and Radiation Management Administration (editor’s note: this agency split into various programs a few years ago and is defunct), so call them with complaints.

And so another column ends. At least I got to learn seven new ways to say “poop” and not get edited. And I learned more about the invaluable if somewhat disgusting and often smelly service provided by the wastewater plant. So thanks again to the nice folks in the Baltimore City Department of Public Works for allowing us to live free of our own filth and, at the same time, preserving life on Earth as we know it.

I see these everyday on my way to school.

I have always been wondering what that was!

Pingback: 15 Things I’d Rather Do Than Go See 'The Butler' | Kill The Girls.comKill The Girls.com

just 1 word “WOW”

This was a most entertainingly informative article. Thanks for the chuckles and knowledge. Now I know where when I go, goes.