We just came across this self-described “very subjective” guide to Baltimore underground press titles on microfilm that John Duda published in the Indypendent Reader. – BoL

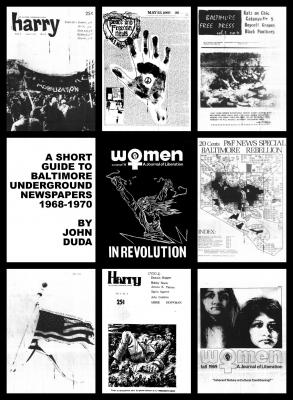

A Short Guide to Baltimore Underground Newspapers (1968-1970)

By John Duda (Indypendent Reader, Winter 2009/2010 – Issue 13)

[John is a member of the Red Emma’s Bookstore Coffeehouse Collective and is finishing a PhD at the Humanities Center at Johns Hopkins on the history of the idea of self-organization.]

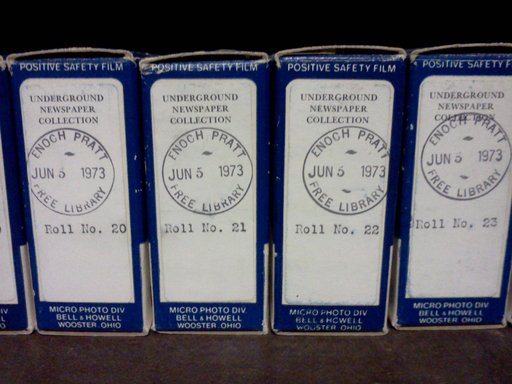

This is a very subjective overview of one of the most productive two-year slices in the history of the Baltimore underground press, as represented by the four newspapers included in the Underground Press Syndicate’s microfilm collection, produced in 1973. As Chuck D’Adamo notes elsewhere in this issue, the Alternative Press Center’s archives, housed at UMBC, make it possible to fairly easily dive much deeper into the history of underground newspapers in the area and beyond. For the casual investigator, however, the UPS microfilm collection is a much easier place to start—in addition to the copies held at most university libraries in the area, the periodicals department at the Enoch Pratt Free Library makes this available for easy consultation by the general public. The 68 rolls of microfilm in the UPS collection cover an amazing range of underground print projects drawn from the entire globe. Of the hundreds of newspapers in the collection [which is also known as the “Underground Newspaper Collection” or UNC], four were produced right here in Baltimore—Peace and Freedom News, the Baltimore Free Press, Harry, and Women. While not every issue of all of these papers made it onto the microfilm rolls, and while some underground papers (like Dragonseed) are entirely missing, what is there is a pretty amazing four-decades-old time capsule from Baltimore’s countercultural left.

This is a very subjective overview of one of the most productive two-year slices in the history of the Baltimore underground press, as represented by the four newspapers included in the Underground Press Syndicate’s microfilm collection, produced in 1973. As Chuck D’Adamo notes elsewhere in this issue, the Alternative Press Center’s archives, housed at UMBC, make it possible to fairly easily dive much deeper into the history of underground newspapers in the area and beyond. For the casual investigator, however, the UPS microfilm collection is a much easier place to start—in addition to the copies held at most university libraries in the area, the periodicals department at the Enoch Pratt Free Library makes this available for easy consultation by the general public. The 68 rolls of microfilm in the UPS collection cover an amazing range of underground print projects drawn from the entire globe. Of the hundreds of newspapers in the collection [which is also known as the “Underground Newspaper Collection” or UNC], four were produced right here in Baltimore—Peace and Freedom News, the Baltimore Free Press, Harry, and Women. While not every issue of all of these papers made it onto the microfilm rolls, and while some underground papers (like Dragonseed) are entirely missing, what is there is a pretty amazing four-decades-old time capsule from Baltimore’s countercultural left.

PEACE AND FREEDOM NEWS Microfilm Roll #12, 4/1968,5/1968,6/1968, 8/1968

Peace and Freedom News was Baltimore’s first underground newspaper, and was firmly rooted in the activist counterculture opposing the Vietnam War. It was published out of the “Peace Action Center” (at 2525 Maryland), a center for anti-war organizing and draft resistance supported by the Baltimore radical community through a voluntary “peace tax” graduated according to income. The issues present in the collection explore some of the most interesting issues of the day. For instance, the April 25 issue deals in depth with the wave of urban rioting that had rocked the US starting in the mid-1960s, and which came to Baltimore in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier that month. Articles include an extended photo essay on the riots in Baltimore and a review of the report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (the “Kerner report”). The May 23 issue came out just six days after the famous anti-war civil disobedience action at the draft board in Catonsville, and featured extended coverage both of the action itself and the larger struggles against conscription and militarism. Besides the revealing radical perspectives on these and other well-known historical events, the paper (along with the two other locally focused Baltimore underground papers discussed here, the Baltimore Free Press and Harry) includes a wealth of incidental detail which allows today’s reader to get a sense for the historical geography of Baltimore resistance and subversion. In addition to the Peace Action Center, the New Era Bookshop (at 408 Park) features prominently in the accounts of day-to-day organizing and political education. The May 23 issue includes owner Bob Lee’s account of the second right-wing attack on the shop. A thriving network of countercultural stores and coffeehouses, largely in either Mt. Vernon or in the area around 25th St. in what today we’d call lower Charles Village, seemed to make up the bulk of the paper’s advertisers. In particular, the “Crack of Doom” coffeehouse (at 103½ 22nd St.) was teeming with everything from political lectures to poetry to avant-garde film.

BALTIMORE FREE PRESS Microfilm Roll #5, 5/31/1968, 10/1/1968, 10/11/1968

The Baltimore Free Press (BFP) picked up basically where Peace and Freedom News left off, proclaiming itself in the masthead as “Baltimore’s Remaining Underground Newspaper.” BFP was a part of the “Liberation News Service”, a radical left Associated Press of sorts, launched in 1967, that distributed articles and photographs to and between different underground presses in the US. In style and content, the Baltimore Free Press was pretty close to Peace and Freedom News—with articles exploring post-riot Baltimore racial politics, the Black Panther Party, and the Catonsville 9. Besides drawing on the counterculture for the advertising revenue needed for keeping the paper afloat, the BFP seemed to include more content devoted to underground arts and culture. A large article exploring the work of Beat author and drug fiend William S. Burroughs appears in one issue, alongside the “Silver Screen” column penned by none other than local film hero John Waters.

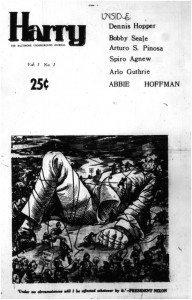

HARRY Microfilm Rolls #36 and #57, 22 issues in total from 1969-1970 with a few gaps.

Harry is easily the best-represented paper out of Baltimore in the UPS’s microfilm collection, and in many ways, the most interesting. Harry, subtitled “Baltimore’s Underground Journal” and published by Atlantis Publishing out of an office at 233 E. 25th St., was decidedly a countercultural paper first and foremost, with a heavy focus on the psychedelic underground of Baltimore arts and culture. In the first issue, in 1969, we get coverage of the first annual Read Street Fun Festival—a miniature Woodstock of sorts in Mt. Vernon. A regular film column ran alongside many music articles, like the January 22, 1970 article which sought to define the “Baltimore Sound” in the small but apparently thriving independent local music scene: “you take a bunch of kids born in the ’40s and early ’50s, shovel the Supremes, the Dells, Otis, Aretha, the Temptations, Smokey Robinson, and all the others down their throats for 10 to 15 years, then turn them on to psychedelia, dope, meditation, folk, blues, rock, and all the other hippie paraphernalia, give it a couple of years to get together, and you get a very strange mixture of music. Hard driving drums, follow the bouncing ball bass, screaming guitars driven by a wall of amplifiers and a desire to feel music instead of just hear it—1,000-2,000 watts who cares, turn it up, more, more.…” Many issues featured a full-page comic from Gilbert Shelton’s “Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers.” And the back page of the newspaper, “Nothing Ever Happens in Baltimore”, was a comprehensive guide to the next two weeks of underground culture. It’s here that we start to see the transition between “underground newspaper” and “alternative weekly” taking shape—overall, reading back through Harry one gets the sense that this was much less the unofficial paper of record for a social movement than P&FN or the BFP. Or rather that is was that, but also something else, the beginning of a guide to commodify your dissent, as Tom Frank so aptly put it. Hence the slick ads for movies and music produced by large studios and record companies which appear in Harry’s pages—the counterculture was becoming less of a threat to capitalism and more of a way to cash in on youth disaffection. That’s not to say that everyone involved with Harry was an opportunist excited by the fun of the underground lifestyle getting their journalistic feet wet before moving on to more profitable pursuits in the culture industry—like for instance P.J. O’Rourke, who worked with the paper before turning away from left-wing politics and metamorphosing into a court jester for the libertarian Right. (Or, for that matter, a police infiltrator, as Chuck D’Adamo details elsewhere TK!) The same radical political projects and spaces that appear in the pages of the first two papers discussed appear again in Harry, along side new ones—like the February 5, 1970 announcement of the Baltimore Free University (a kind of community extension at Johns Hopkins run by radicals). The paper covers the “Balto Cong,” a Maoist/national liberation youth direct action brigade. Sadly, the only overview of just what the Balto Cong was I could find was O’Rourke’s self-serving and deeply dismissive account in his Give War a Chance. The paper printed dispatches from Baltimore Black Panther Party Lieutenant of Information Chaka Masai, covered the April 1970 anti-war actions at Johns Hopkins (in which Homewood House was surrounded by demonstrators), provided first-hand testimony of the May 1970 Flower Mart police riot when Harry reporter Tom D’Antoni got swept up the mass arrests made in Mt. Vernon place. And prominent draft resister Dave Eberhardt (one of the Baltimore Four) was a frequent contributor. A special insert from the “Baltimore Ecology Center” outlined a nascent program of environmentalism. So despite the contradictions, Harry’s relatively long run and broad focus makes it an invaluable piece of the historical record for anyone curious about social movements in Baltimore during the late 1960s and early 1970s.

WOMEN Microfilm Rolls #68 (the Pratt online finding aid is wrong!), First six issues 1.1 (Fall 1969) through 2.2 (Winter 1970).

Women is a departure from the other papers in the collection. Rather than a local newspaper, Women was a quarterly nationally distributed journal on newsprint, with each issue thematically investigating some aspect of the new feminist critique that had been incubating within (and against some tendencies within) the New Left. Issue topics included women’s history, women in the arts, revolutionary women, and “how we live and with whom”(breaking open the domestic straightjacket) and featured articles like Roxanne Dunbar’s “Poor White Women.” While not embracing the underground aesthetic of cheap thrills and psychedelic intoxication prevalent in some of the other papers in the collection, Women was also deeply concerned with cultural production—I’d estimate one-half to one-third of each issue was set aside for poetry and art. Despite being aimed at a nationwide audience, Women nevertheless reveals quite a bit about feminist organizing in Baltimore at the time. The journal was published by Baltimore Women’s Liberation, whose 50+ members sought to provide, in addition to information and theoretical perspectives, practical services like abortion and childcare as well as pursuing a project of working class organizing. The Spring 1970 issue’s contributor list gives you a sense of the diversity of Baltimore’s feminist community, listing local contributions from Marilyn O’Connor (who many of us still count as a friend and ally in the lower Charles Village neighborhood!), Jennie Bull (an organizer of the Learning Action Center, another experimental education project), Kay (“kind of small, not very tall. Just plain Kay, but that ain’t all.”), Barbara McKain (“maoist-liberal librarian”), Beryl Jones (“factory worker”), and Joyce Williams (“high school student”). The paper also provides some insights into the 1970 founding, by Baltimore Women’s Liberation and the Baltimore Defense Committee, of the People’s Free Medical Clinic at 3028 Greenmount Ave.—one of the few projects in the pages of the archive to have survived to the current day, albeit in modified form as the People’s Community Health Center.

Help Save Social Movement History!

Obviously, this is only scratching the surface of both the Baltimore underground press and the history of local social movements in the late ’60s and early ’70s—and this is important history that’s in danger of disappearing! There’s really no good reason why this essential printed historical record is hidden away on microfilm rather than available online. If you’ve got back issues you’d like to lend the Indyreader so we can scan and post them, please get in touch at indypendentreader@gmail.com. Likewise, if you’d like to help us fill in the details of some of the history we’ve touched on above, send us your recollections and we’ll post them online as supplemental content to accompany this issue.

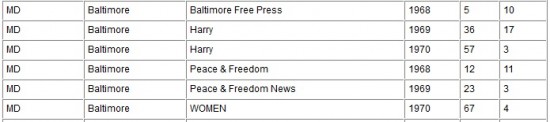

Click here to see a listing of all underground newspapers from 1963-1970 on microfilm at the Enoch Pratt Free Library. A guide to Pratt’s local underground press titles is shown below; the last two columns represent the microfilm roll # and section (e.g., “Baltimore Free Press” is on Roll #5, Section 10).

[Another Baltimore underground paper, “Dragonseed” (published in 1972 at 1623 Bellona Avenue), can be found at UMBC’s Kuhn Library. According to the Indypendent Reader (“From Underground Press to Indymedia“), “Its contributors included peace activist Dave Everhardt, and Bob Goren—who later helped found The Plain Talker in 1975, an activist monthly newspaper. But most of the bylines in Dragonseed were simply first names or noms de plume. The coverage here was a bit more community-based than Harry; you find articles on farm workers boycotts, utility rate hikes, the Baltimore Experimental High School, but also Watergate, the 1972 protests at the RNC, and the campaign of George McGovern.” – BoL]

See also:

“The New Harry (May 1991)” (Accelerated Decrepitude)

“Harry: Baltimore’s Underground Journal Debuts (1969)” (Baltimore Or Less)

“The Willful Power of Make-Believe” (P.J. O’Rourke writes about his “Harry” days in in Peter Stine’s The Sixties)

Underground Newspapers on Microfilm 1963-1970 (Enoch Pratt Central Library)

Underground Press – Maryland (WorldCat)

very awesome!

This is going to sound bizarre because it is and does to me as well.

I woke up this morning and my immediate first thought, entirely unpremeditated was,, I wrote for the Baltimore free press. (!?)

I’ve never been to Maryland, don’t read or think about it.

I began researching and lo and behold there was such a thing as the BFP and your web page tells the tale.

Do you know any of the names of the writers at the BFP?

Pingback: Old World Underground, Where Are You Now? Sixties Underground Press and the Digital Age – Libraration News Circus