by Lisa Greenhouse

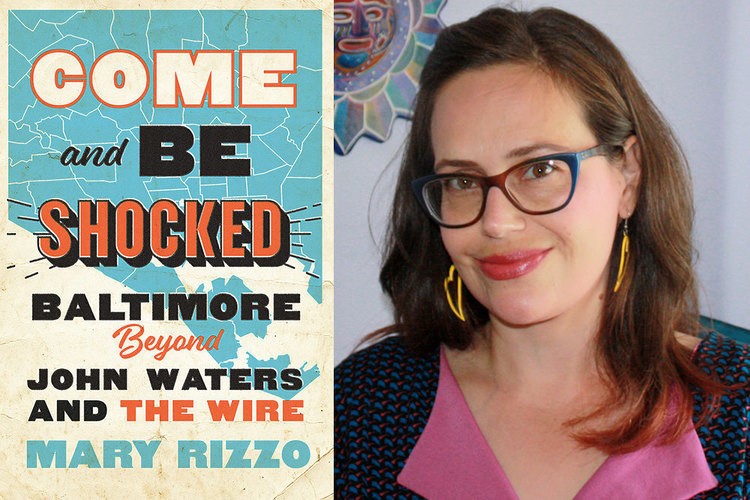

Outside Looking In: Mary Rizzo looks at Baltimore beyond the charm and the harm

What do outsiders imagine when they think of Baltimore? Mary Rizzo’s absorbing new book, Come and Be Shocked: Baltimore Beyond John Waters and the Wire (JHU Press, 2020), examines what she considers the two primary portrayals of the city. Rizzo, an Assistant Professor of History at Rutgers University, looks at several of the more well-known cultural productions that have depicted Baltimore over the last sixty years, finding contrasting themes that have emerged from a highly segregated city. According to the author, we are given two dominant portrayals: incompatible, incomplete, and only one seen as usable by a city government intent on constructing an image of Baltimore attractive to tourist dollars and investment in a post-industrial economy.

On the one hand, we have “Charm City,” a vision of Baltimore which stars “the Hon,” a fun stereotype of white, working-class, Southern womanhood that is “friendly, quirky, charming, and sassy.” This is an image that fits well with city promotional efforts and so has been bear hugged by the powers that be. The irony that an image drawn from working-class culture would be used to attract professionals and capital to a city whose working class had been devastated by the destruction of blue collar jobs in a period of globalization is not lost on Rizzo.

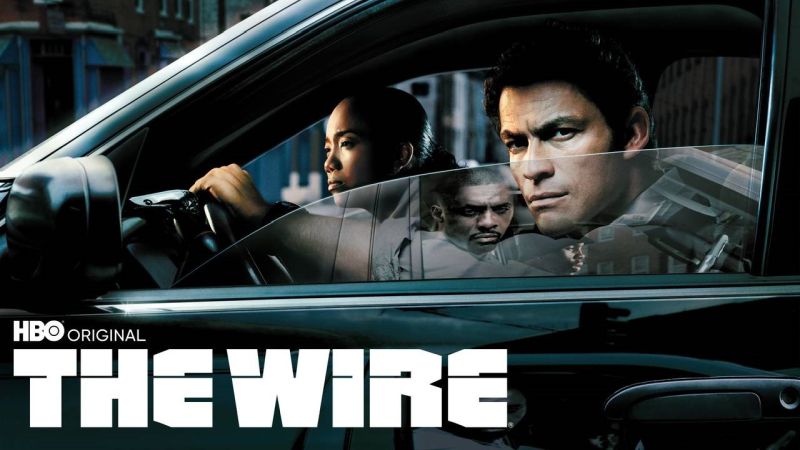

The other image is of Baltimore as a dangerous place. “The city that bleeds.” “Bodymore, Murdaland.” This is an image that was purveyed by shows like Homicide and The Wire and by an indigenous form of music – club music – which found popularity beyond the city limits and so shaped perceptions of Baltimore. The local establishment strove to suppress this image.

Rizzo’s analysis of filmmaker John Waters’s local meaning is particularly interesting. Rizzo points out that Waters has been looked at in the context of queer studies but not in the context of urban studies. However, in the 1960s, a young Waters took advantage of Baltimore’s urban renewal machinery by filming norm-violating acts in lightly surveilled areas of the city that had been abandoned to imminent urban renewal. His whiteness helped him get away with it. Often the shocked (or at least surprised) expressions of black bystanders served as a foil for his actors.

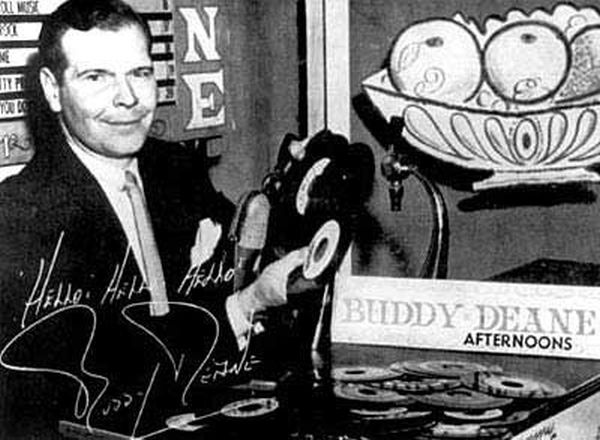

Hairspray (1988) was the first film in which Waters tackled racial inequities, but even so, the civil rights effort portrayed there was spearheaded by a white person: Tracy Turnblad (Ricki Lake). Hairspray celebrated the underdog: the black dancers who were excluded from the Corny Collins Show (based on Baltimore’s real Buddy Deane Show) and Tracy herself, who was overweight and ridiculed by the other dancers.

Hairspray’s “Corny Collins Show”

According to Rizzo, however, many critics and fans seemed drawn more to the quirky early 1960s Baltimore set than to the racial struggle pictured, especially as the subsequent iterations of Hairspray hyperbolized Baltimore’s white working-class cultural characteristics more and more. In fact, the image of Charm City presented by Baltimore planners and promoters drew heavily on John Waters just as the Hon stereotype drew on Waters’s character Divine. While Waters’s initial intent was to violate social norms, his vision of Baltimore was eventually co-opted by the marketers of the post-industrial city. Transgression became quirkiness in this travel magazine version of Baltimore.

Meanwhile, a parallel misapprehension occurred over in deadly “Bodymore.” Fans of The Wire were often more focused on its portrayal of the glamorous gangster lifestyle than on the show’s depiction of structural racism and political corruption. And by neglecting to showcase positive efforts by community organizations in the Baltimore ghetto, the show shaped an exaggerated view of a dangerous city, broken beyond repair.

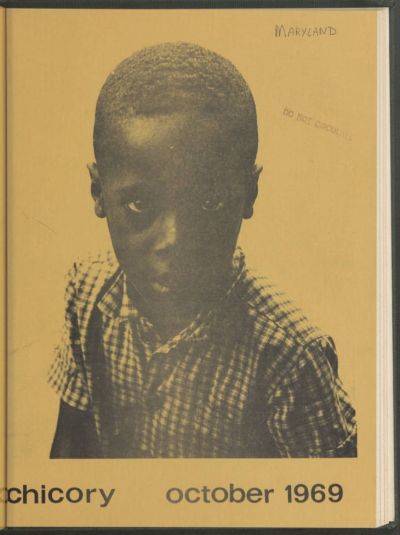

Rizzo finds a truer picture of Baltimore in the street magazine Chicory – published beginning in 1966 by the Enoch Pratt Free Library and initially funded by the federal War on Poverty initiative. Chicory contained poetry and snippets of conversation collected from black community members between 1966 and 1983. Rizzo analyzes the purposes served by the publication for its liberal supporters as well as the purposes met for its contributors. For its funders and sponsors, Chicory provided a window into the black ghetto as well as a pressure release valve. For its contributors, Chicory provided a public forum where ideas and visions could be shared.

The author looks at the role history plays in the creative works she examines as well in the city’s promotional campaigns. Hairspray, while being the first popular film produced for a white audience to deal with Baltimore’s racist past, ultimately whitewashes it by changing the outcome of the actual struggle on which it was based. The Buddy Deane Show eventually went off the air rather than integrate while Waters’s Corny Collins Show integrates in a made-for-Hollywood happy ending.

Other films from the period with depictions of Baltimore, such as Barry Levinson’s Diner and Tin Men, ignore the existence of racism and, according to Rizzo, nostalgically portray the early 1960s as a golden era. Likewise, city planners and boosters pushed racism out of sight, emphasizing historical artifacts that fit with their image of Charm City. Rizzo writes that in these types of city promotional efforts, “history, at best, can be mobilized to give symbolic value, but it is not truly valued.” History lay in the path of “a municipal hype machine that swept growing racial inequality under the rug of marketing campaigns, inoffensive art, and stories about eccentric white people.”

Related Links:

Listen to “Writers LIVE!: Mary Rizzo”

Watch “Writers LIVE!: Mary Rizzo”