By George Gipe (The Baltimore Sun, 10/14/1973)

An Afternoon’s Diversion in the Good Old Days

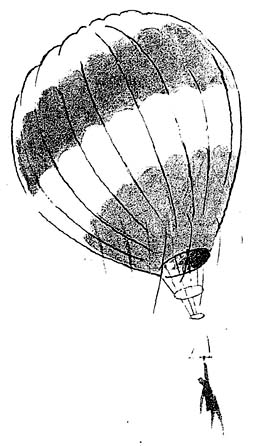

John August, balloon acrobat, gives a memorable final performance

Sunday, September 9, 1905: A half mile above the row houses of East Baltimore, 25-year-old John August twisted in the air and pulled himself to a sitting position on the trapeze bar. It was a pleasant day, the last of the Industrial Trades Exposition.

Sunday, September 9, 1905: A half mile above the row houses of East Baltimore, 25-year-old John August twisted in the air and pulled himself to a sitting position on the trapeze bar. It was a pleasant day, the last of the Industrial Trades Exposition.

Below August, nearly 10,000 spectators jammed Highlandtown’s street to watch the “aeronaut.” Others sat in chairs on rooftops or craned their necks from streetcars. As far away as the upper floors of the Belvedere Hotel, people gently nudged each other aside to obtain a better view of the man’s athletic skill and derring-do.

“Just before coming to Baltimore,” explained Calvin Raglan, treasurer of the Industrial Trades Exposition Company, “I advertised for a balloonist. There were several applicants, but John August was the only one who promised to do acrobatic stunts in the air. He was the best aeronaut I ever saw.”

To the crowd’s delight, August suddenly dropped from his sitting position, pitching downward for a split second until his bands reached out to squeeze the trapeze bar. A shout of approbation rose from a streetcar at the corner of Broadway and Lancaster street. George G. Wolf, watching the performance as he had every day for a week from his home at 8th street and Eastern avenues. thought the aeronaut seemed more daring than usual.

“August said he wanted this exhibition to be the best he had ever given.” Calvin Raglan said later. “He was in the best of humor. I offered him his salary before the ascension but he said he did not want it until he came down. The day was an ideal one, and to aid him in his feat August had the balloon inflated from gasoline instead of smoke, to enable him to rise more rapidly.”

John Berghammer, of East Lombard street, sitting with his family in the yard, saw John August drop one hand to his side, then wave it for the crowd’s attention. “Some of my friends told me that before going up he drank six pints of beer,” Berghammer remarked. “He wanted to be nerved for a great performance. I know that he had taken a little before the other ascensions.”

“August was what you would term a good fellow and was well-liked by all of the members of the exposition,” Mr. Raglan said. “I have always thought he came to us from St. Louis, where he was engaged in this kind of business. I think his parents live in Shenandoah, Pa. He never dressed in tights but wore ordinary clothes while in the air.”

As light applause sifted through the late afternoon breeze, John August reached upward to secure the trapeze bar with both hands. His act was not a particularly intricate or sophisticated one, but it required nerve—nerve for which he was paid $150 a week. “It was,” he remarked on one occasion, “better than working for a living.”

Tightening his grip, he seized the bar with both hands and attempted to pull himself up. In mid-swing, something happened to his arms. Refusing to obey, they dropped him back to the dangling position. A rustle of apprehension moved through the crowd below.

“When I saw him fail in his first attempt to circle the bar I knew it was all over,” said H. E. Chase, president of the Structural Trades Alliance. “I was impelled to call to him, as though my voice could be heard so high in the air.'”

“Again and again he swung his body up toward the almost invisible bar,” one reporter wrote. “He even endeavored to husband the strength of his left hand by banging from his right and then making another effort to swing himself upward. A prayer went up from the watchers in the short space of time that elapsed in these movements . . . people waited in a horror-fascinated expectancy for the fatal drop…”

August held the trapeze bar with an ever-weakening grip. Nearly a minute passed, then “suddenly the aeronaut let go,” the reporter continued. “At first the body seemed to fall slowly, so high was he in the air. The body assumed a slanting position, with the arms and legs stretched out and swaying. Then as it drew nearer the earth, the figure turned over and over with great rapidity.”

“When he was about 2,000 feet in the air,” George Wolf said, “I thought something was wrong. August seemed to be endeavoring to reach his parachute and then, an instant later, I saw him drop. At first I thought he might have cut himself loose but in that same instant I knew that he had fallen. The balloon continued to rise another thousand feet before it fell…”

“We saw at that time that the balloon was wobbling and veering a great deal and discharging large quantities of smoke, which meant that much of the hot air was leaving it,” the Broadway streetcar conductor added. “It was descending at a rapid rate and it appeared to us that the web of the balloon had entangled the parachute ropes. The parachute, however, was open and our idea was that if it were disengaged the man might save his life. As it was, the balloon and the aeronaut descended and got beyond our vision before we could learn if they were descending with sufficient speed to kill the man. . .”

Mrs. August J. Wise, 424 Cough street, Highlandtown, was standing in her kitchen at the time. “I was playing with our little baby,” she said, “when I heard a whizzing noise, but couldn’t tell what was the matter. As I looked up I saw something strike the fence in my yard, only 4 feet from where I was. To my horror, I saw that it was the body of a man and I knew at once that it was the balloonist.”

For the rest of that day and most of the next, thousands of Baltimoreans traveled miles to visit the Wise yard. Even after John August’s remains were taken away they came to stare at the crushed fence and listen to the boasts of next-door neighbor William Haebel, who proudly told reporters he was the “first to touch the remains.” On Monday, September 10, the Canton police station was also mobbed by those who wanted a glimpse of the shattered corpse. In death, John August was far more celebrated than alive as for a week afterward, few persons talked of any topic but his half-mile fall. There is no record of any outcry that the obviously dangerous “sport” be regulated, curtailed or abolished.

So ends the story of John August, a man who gave the people of those “good old days” what they secretly wanted.

Pingback: John August, balloon acrobat of the early 1900s | A ton of useful information about screenwriting from screenwriter John August